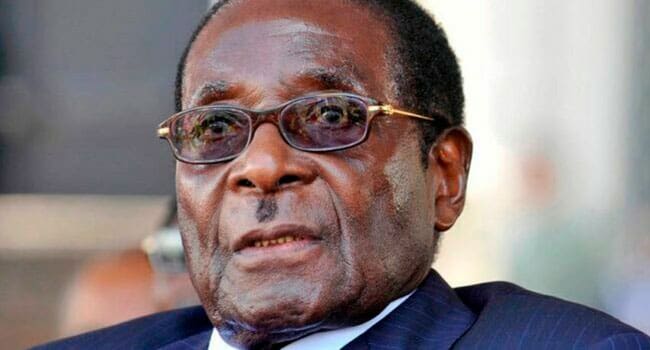

Some years ago, I was having lunch with my favourite aunt when she brought up the topic of Robert Mugabe. Zimbabwe’s evolving storyline was troubling her.

Some years ago, I was having lunch with my favourite aunt when she brought up the topic of Robert Mugabe. Zimbabwe’s evolving storyline was troubling her.

The Catholic charity she was involved with had adopted Zimbabwe as one its projects and Mugabe had been seen as a good guy. You could even say he was a hero to her.

It’s easy to understand why.

As an ardent Irish nationalist, my aunt identified with Mugabe’s earlier role in the struggle for independent black majority rule. And helping Africa had long been a part of the Irish Catholic tradition.

But when she shared her misgivings about how things were developing, I wasn’t sympathetic. Mugabe, I said, had always been a thug. That didn’t go down well.

Robert Mugabe was born in 1924 in what was then Southern Rhodesia. When his father abandoned the family during his childhood, an Irish Jesuit priest became something of a replacement parental figure. No doubt, knowledge of this connection played a part in my aunt’s bonding process.

A teacher by profession, Mugabe acquired three degrees in the 1950s. He also became caught up in the wave of anti-colonial African nationalism, adopting the Marxism that was fashionable in many academic and political circles.

Then, as political agitation morphed into armed insurrection and Mugabe advanced into a leadership role, prison inevitably beckoned. There were two jail terms, totalling almost 11 years.

After he was released in 1974, Mugabe fled to Mozambique and became a key figure in the guerrilla war against Ian Smith’s white-minority Rhodesian regime. Finally, an internationally-orchestrated settlement was reached, Rhodesia was transformed into Zimbabwe, an election was held and Mugabe became prime minister in April 1980.

Substantially conducted along tribal lines, the election that brought Mugabe to power was characterized by widespread charges of voter intimidation. There were even suggestions the result should be annulled. But it wasn’t. Mugabe’s tribe – the Shona – constituted more than two-thirds of the population and the result of an election conducted by Scandinavian standards wouldn’t have been radically different.

And initial prospects for the new country seemed auspicious. Acknowledging that he’d inherited the “jewel of Africa,” Mugabe proposed to govern in a conciliatory style. Many of the newly independent African states had messed up badly over the preceding two decades; there were lessons to be learned and mistakes to be avoided. Mugabe was going to do it right.

In particular, he set out to reassure the small white minority. Recognizing that their skills were vital – especially in the critical commercial farming area – Mugabe wanted to avoid wholesale white flight.

But when the first worrisome sign appeared within a couple of years, it had nothing to do with black-white relations. Instead, it was a matter of power politics leavened with tribal animosity.

Tribal warfare had been a feature of pre-colonial times and one of the flashpoints pertained to the majority Shona and the minority Ndebele. Mugabe was Shona and his chief rival, Joshua Nkomo, was Ndebele.

As tensions erupted into violence, Mugabe formed the predominantly Shona Fifth Brigade – trained for him by the North Koreans – and turned it loose on the Ndebele provinces of Matabeleland. Estimates of fatal casualties vary, going as high as 20,000, many of whom were civilians.

Souring relations with the white community hit bottom in 2000 following a wholesale confiscation of white-owned commercial farms, the majority of which had been purchased post-independence. Unsurprisingly, there was major economic fallout. Production of staples like maize and wheat plummeted, and the previous “grain basket of southern Africa” became a food importer.

With the economy collapsing, Mugabe resorted to printing money, which produced the inevitable rampant inflation. And with economic misery widespread, it became necessary to steal elections.

But it was to no avail. To quote opposition politician Tendai Biti: “The regime can rig elections but they can’t rig the economy.”

Now, as Mugabe departs from power, we’re left with what the New Statesman’s Martin Fletcher called “the tragedy of Robert Mugabe – the architect of Zimbabwe’s independence who has reduced it to penury; the guerrilla leader who freed his country from white-minority rule only to subject it to far greater repression.”

Was Mugabe always a thug?

It’s hard to know for sure, but one can safely say this: once ensconced in power, thuggery came easily to him.

Pat Murphy casts a history buff’s eye at the goings-on in our world. Never cynical – well perhaps a little bit.

The views, opinions and positions expressed by columnists and contributors are the author’s alone. They do not inherently or expressly reflect the views, opinions and/or positions of our publication.