The public mood was optimistic when I first came to Canada, what with the impending Centennial year celebrations and the overall sense that things were good and could only get better. And part of that feeling was an emerging pride in past nation-building, particularly the transcontinental railroad linking the Atlantic to the Pacific. It was 130 years ago this month – on November 7, 1885 – that the railroad’s ceremonial last spike was driven in Craigellachie, British Columbia.

The public mood was optimistic when I first came to Canada, what with the impending Centennial year celebrations and the overall sense that things were good and could only get better. And part of that feeling was an emerging pride in past nation-building, particularly the transcontinental railroad linking the Atlantic to the Pacific. It was 130 years ago this month – on November 7, 1885 – that the railroad’s ceremonial last spike was driven in Craigellachie, British Columbia.

You’d expect historians and writers of weighty magazine pieces to be dutifully enthusiastic about the transcontinental railroad. And they were. But in the mid-60s, that enthusiasm also extended into the popular culture.

For instance, on January 1, 1967, the CBC broadcast a specially commissioned song from Gordon Lightfoot, then a rising folk singer. Called the Canadian Railroad Trilogy, it was an epic running over six minutes and deploying an unusual structure that alternated fast and slow tempos. And while it had its sombre moments, the overall narrative was heroic.

Then, a few years later, writer Pierre Berton told the story in a pair of well received and very popular books – 1970’s The National Dream and 1972’s The Last Spike. A skilful storyteller rather than an academic historian, Berton, like Lightfoot, caught the uplifting, patriotic mood.

And it really was a heroic story, one illuminated with large personalities and monumental challenges. Building what was then the longest railroad in the world across 5,000 kilometres of sparsely populated, intensely rugged and often downright inhospitable terrain, it was an undertaking initially described by the Liberal opposition as “an act of insane recklessness.” But Canada’s first prime minister, the Tory John A. Macdonald, was for it, and it had been a condition British Columbia insisted on when joining Confederation.

The western section of the line, linking Ontario with the Pacific, was by far the most difficult part, so much so that actual construction didn’t begin until May 1881. And the vehicle for building was the newly formed Canadian Pacific Railway (CPR), a syndicate headed by two Scottish-born cousins, Donald Smith and George Stephen. Smith was, among other things, chief commissioner of the Hudson’s Bay Company, and Stephen was president of the Bank of Montreal.

Although the CPR was a private venture, its scope was sufficiently large and its prospects sufficiently risky that substantial government assistance was required. There was $25 million in cash, 25 million acres of public land, millions of dollars’ worth of existing publicly owned rail lines and completed survey costs, and a guaranteed monopoly on western traffic – all followed by a further $22.5 million loan. Even then, Stephen was forced to go to London in 1885 to secure additional financing to finish the job.

Of all the personalities involved, perhaps the most spectacular was an American, William Cornelius Van Horne from Illinois. As a vastly experienced railway man who’d left school at the age of 14, Van Horne’s particular forte was getting difficult stuff done, in which capacity he was brought in as the CPR’s general manager in 1882.

Theodore Regehr’s biographical sketch describes him as a physically imposing man who liked big things, had a keen eye for detail and was gifted with exceptional energy. And Van Horne apparently saw himself as the “boss of everybody and everything,” which was perhaps a necessary requirement for the situation. In any event, he did what he was hired to do.

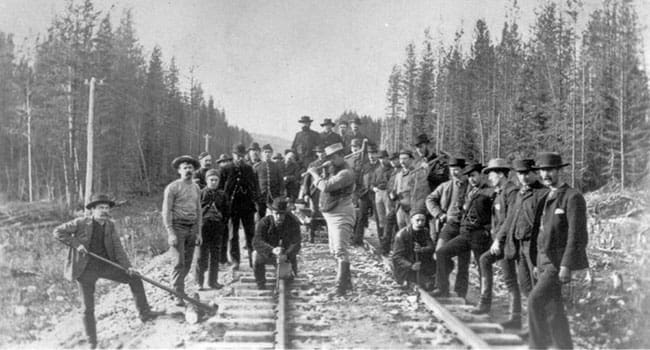

Of course, building the transcontinental railroad also required the efforts of many people whose names are lost to us now. If you like, the little guys – the navvies – who swung the hammers and endured the blazing sun and the numbing cold, not to mention the risks to life and limb. And prominent among these were the imported Chinese labourers who did some of the most dangerous work, blasting through the mountains of British Columbia.

Lightfoot, to his credit, succinctly catches the navvy spirit: “A dollar a day and a place for my head/A drink to the living, a toast to the dead.” It was indeed a different world.

Canadian history is often described as bland and boring, particularly when compared to the tumultuous events elsewhere. While others were defined in the crucible of revolution or civil war, our transforming events were as mundane as building a railroad. I don’t know about you, but I’m cool with the contrast.

Pat Murphy casts a history buff’s eye at the goings-on in our world. Never cynical – well perhaps a little bit.

The views, opinions and positions expressed by columnists and contributors are the author’s alone. They do not inherently or expressly reflect the views, opinions and/or positions of our publication.