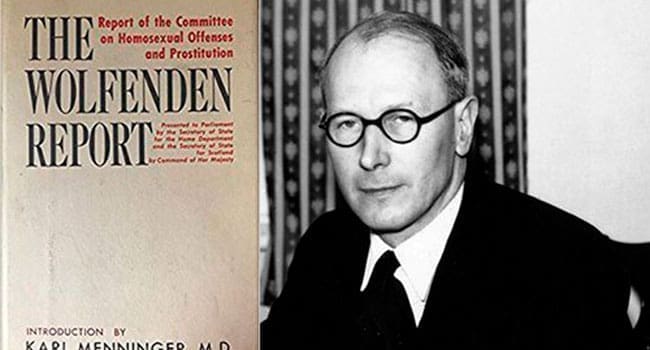

In August 1954, the British government tasked a committee to look into the law on both homosexual offences and prostitution. Chaired by Sir John Wolfenden, the committee set to work on Sept. 15, 1954, and its recommendations were published just under three years later.

In August 1954, the British government tasked a committee to look into the law on both homosexual offences and prostitution. Chaired by Sir John Wolfenden, the committee set to work on Sept. 15, 1954, and its recommendations were published just under three years later.

Known to history as the Wolfenden Report, it’s remembered as an influential first step towards changing legal and social perspectives on homosexuality, not only in Britain but in the English-speaking world.

Homosexual activity between males was illegal in Britain, although there was no corresponding prohibition on sexual relations between women. This distinction, mind you, had less to do with tolerance than with naiveté. Lesbianism just wasn’t something that most people were particularly aware of.

When the report hit the street in September 1957, it raised a lot of eyebrows. Cutting against viscerally entrenched popular attitudes, it was going to be a hard sell.

Wolfenden and his colleagues didn’t endorse or idealize homosexuality. They took the position that as long as it transpired between consenting adults in private, the law should stay out of it. There “must remain a realm of private morality and immorality which is, in brief and crude terms, not the law’s business.”

That distinction remains problematic to this day – albeit no longer for considerations pertaining to sexuality. Just because public opinion finds something offensive doesn’t necessarily mean it should be illegal. Being scandalized or outraged by someone’s behaviour isn’t sufficient reason to put them in jail. Sins and crimes may overlap, but they’re not synonymous.

And there was a further regard in which Wolfenden leaned against the winds of consensus. Contrary to much of the prevailing psychiatric wisdom, the report declined to view homosexuality as a disorder. To quote, “homosexuality cannot legitimately be regarded as a disease, because in many cases it is the only symptom and is compatible with full mental health in other respects.”

It took a decade for the Wolfenden recommendations to be enacted into law. For England and Wales, the Sexual Offences Act 1967 decriminalized consensual homosexual activities between two men as long as they took place in private and the participants had attained the age of 21. As for the rest of the United Kingdom, the law was changed in Scotland in 1980 and in Northern Ireland in 1982.

In the years leading up to the change, sympathetic depictions were conspicuous by their cinematic absence. The 1961 movie Victim – reputedly the first time the word “homosexual” was used in the English-language cinema – was one of the rare exceptions.

Victim was a “modest, tight, neat little thriller” about an “upwardly mobile barrister with a dark past.” As a married, repressed gay man, the protagonist risked everything to expose a blackmail ring aimed at frightened homosexuals.

Although tame, even downright quaint, by modern standards, Victim had a cutting edge sensibility in its day. In its native Britain, the film censor assigned an X (adults only) rating, while the Motion Picture Association of America withheld its seal of approval.

And there was an interesting twist.

Then an English matinee idol, the movie’s star – Dirk Bogarde – was a deeply closeted gay man. But rather than shy away from the project, he embraced it to the point of rewriting some of the dialogue to render a critical scene more intensely explicit. Given that the scene was where the barrister confessed his sexual inclinations to his wife, you can understand why Bogarde biographer John Coldstream describes it as the moment “when Dorian Gray allowed us with him to take a peep into the attic.”

But daring as it was, Victim pulled its punches. In the words of American film critic Pauline Kael, “the hero of the film is a man who has never given way to his homosexual impulses; he has fought them – that’s part of his heroism.” Today, we’d tend to see it as his tragedy.

Still, caution notwithstanding, it’s reasonable to surmise that Victim had an impact on the British debate. Arthur Gore, the Earl of Arran who shepherded the reform legislation through the House of Lords, certainly thought so.

In June 1968, he wrote Bogarde commending him on “your courage in undertaking this difficult and potentially damaging part.” It had, the earl believed, played a role in moving public opinion.

Pat Murphy casts a history buff’s eye at the goings-on in our world. Never cynical – well perhaps a little bit.

The views, opinions and positions expressed by columnists and contributors are the author’s alone. They do not inherently or expressly reflect the views, opinions and/or positions of our publication.