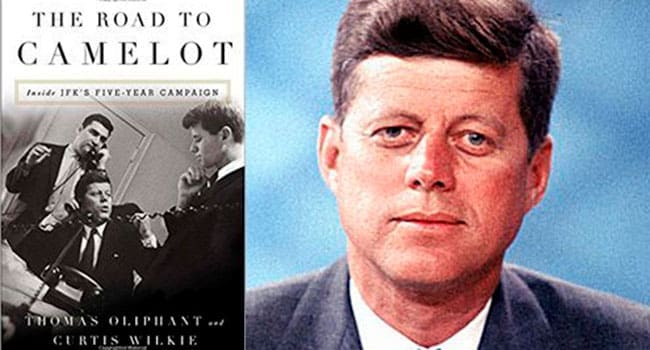

This is John F. Kennedy’s centenary year – he was born on May 29, 1917. And the books keep coming, the latest being Thomas Oliphant and Curtis Wilkie’s The Road to Camelot.

This is John F. Kennedy’s centenary year – he was born on May 29, 1917. And the books keep coming, the latest being Thomas Oliphant and Curtis Wilkie’s The Road to Camelot.

For those who fancy a deep dive into the details of Kennedy’s successful 1960 presidential campaign, the book fits the bill quite nicely. It’s also a good read.

While the authors are veteran journalists and favourably disposed toward their subject, they avoid out-and-out hagiography. And their research has a comprehensive feel to it. In particular, they draw on the vast trove of documents and oral histories housed at the Kennedy Library in Boston.

If you’re familiar with the trajectory of Kennedy’s presidential quest, the book probably won’t add much to your narrative knowledge. But you might still find some of the insights interesting. I certainly did.

Here are a few examples:

The religious issue

Kennedy’s Catholicism is often portrayed as a significant obstacle to his election. Anti-Catholic bigotry, so the story goes, was a major challenge for his campaign.

The reality is more complicated. In fact, Kennedy’s religion was a two-edged sword. It probably cost him in terms of popular vote, but benefited him in the all-important electoral college.

Interestingly, this dichotomy was originally identified by Kennedy’s camp. Working to convince Democratic power brokers that his candidate’s Catholicism wouldn’t be a net electoral impediment, Kennedy aide Theodore Sorensen looked at mid-20th century voting patterns and came to a fortuitous conclusion.

Having a Catholic on the ticket, Sorensen claimed, would work to reverse the post-war drift of the traditional Democratic Catholic vote towards the Republicans. After the election, this assessment was confirmed by MIT political scientists.

It all came down to geographical distribution.

By virtue of being significantly concentrated in southern states, many of the anti-Catholic votes were essentially wasted. Historically-based Democratic strength in the solid south was such that the party could absorb vote losses and still carry the region. Southern anti-Catholicism notwithstanding, Kennedy won Texas, Georgia, Louisiana, North Carolina, South Carolina and West Virginia.

In contrast, Catholic voters disposed to favour a co-religionist were strategically located. The MIT analysis suggests this factor was decisive for Kennedy wins in critical northern states.

The father-son relationship

It’s long been speculated that Kennedy’s wealthy father, Joe, was the real driving force behind the quest for the White House. Initially, hopes were vested in the oldest son, Joseph Jr., but the torch passed when he was killed during the Second World War.

Oliphant and Wilkie tell a different story. Kennedy, while respectful of his father, was his own man.

Yes, Joe was fiercely ambitious for his son, and liberally used money and connections to grease the path. For instance, those who wonder why Time magazine was so kind to Kennedy need look no further than the friendship between Joe and the publisher Henry Luce. Although Luce was Republican, his Time-Life empire had what the book describes as a “love affair” with the Kennedys.

But Kennedy wanted the presidency for himself, not just to satisfy his father. And he was prepared to make his own decisions, even when they went against his father’s advice. Competing in the West Virginia primary – which Joe opposed – is one example.

The first modern politician

For better or worse, Kennedy can reasonably be described as the first modern politician.

In the book’s telling, he was the first presidential candidate to use a pollster on a continuous basis. Beginning in 1958, he engaged Louis Harris to provide ongoing “issues and personalities opinion research.” And in addition to informing campaign strategy, the results were selectively deployed to convince skeptical power brokers of the futility of resistance and the need to board the bandwagon.

Kennedy’s campaign also pioneered the idea of 30-second political commercials. Thanks to him, the concept of image became all-important.

The Eisenhower factor

The popular incumbent president, Dwight Eisenhower, didn’t actively campaign until late in the day. But when he rolled up his sleeves and went to work for Kennedy’s opponent, Richard Nixon, Kennedy was worried: “With every word he utters, I can feel the votes leaving me. It’s like standing on a mound of sand with the tide running out.”

Had Eisenhower pitched in earlier, would the razor-thin election have gone the other way? That’s another of history’s conundrums.

Pat Murphy casts a history buff’s eye at the goings-on in our world. Never cynical – well perhaps a little bit.

The views, opinions and positions expressed by columnists and contributors are the author’s alone. They do not inherently or expressly reflect the views, opinions and/or positions of our publication.