“Canada’s forgotten people” – the Metis – have chosen an independent path to survive. Now, bolstered by recent court decisions in their favour, they are well-positioned to negotiate a long-sought goal: a land base.

“Canada’s forgotten people” – the Metis – have chosen an independent path to survive. Now, bolstered by recent court decisions in their favour, they are well-positioned to negotiate a long-sought goal: a land base.

Rather than wait for further court decisions, Canada should proactively negotiate with Metis people about their rights to self-determination as a distinct Aboriginal people.

The federal government long denied having jurisdiction over Metis. Despite having entrenched constitutional Aboriginal rights, Metis were not seen as a federal responsibility, unlike First Nations and, eventually, the Inuit in 1939. In 1999, the Congress of Aboriginal Peoples (an organization representing off-reserve Aboriginal people) and several Metis and non-status Indians took Ottawa to court, alleging discrimination because they were not considered “Indian” in the constitution.

A 2013 ruling by the Federal Court of Canada in Daniels v. Canada found the scope of the federal power over “Indians and Lands reserved for the Indians” was broad enough that it applied to Metis and First Nations people who do not have Indian Act status. In 2014, the Federal Court of Appeal largely upheld the Daniels ruling, stressing that Metis in particular should be recognized as “Indians” in the constitution.

Now, the matter goes to the Supreme Court, and its ruling should resolve once and for all the issue of whether Metis and non-status Indians fall within the scope of federal powers under Section 91 (24) of the Constitution Act 1867. The court will determine if Metis are “Indians” within the expression “Indians and Lands reserved for the Indians” under Section 91 (24).

Sadly, there has been too much focus on the question of whether the Metis would be entitled to the same federal programs and services available to status Indians. Questions have arisen about the financial strain of granting hundreds of thousands of people access to these federal programs.

One hopes the Metis would be far more interested in negotiating with Ottawa than in programs. Instead, the focus should be on what a new relationship between Metis and the federal government would look like, not just on federal benefits that they may or may be entitled to now.

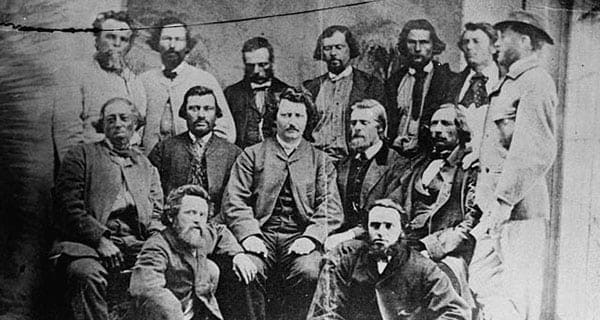

In declaring the need for a provisional government to protect the Red River Settlement, Louis Riel, the Metis icon, purportedly said, “We want to govern ourselves. We will accept no concessions.”

Metis historically demanded self-determination, but unfortunately have lacked the land base to govern over. Only the Alberta Metis have a legislated land base consisting of eight Metis settlements.

Even Metis in Manitoba lost their opportunity at a contiguous territory for a homeland. Under the Manitoba Act, Canada was supposed to grant 1.4 million acres to Metis children, but it failed to deliver. Today, Manitoba Metis are not demanding lost land (which included Winnipeg), but are opting for negotiations with Ottawa.

This is about recognition and reconciliation.

Political scientist Kelly Saunders said that 19th Century Metis did not become “wards of the state” under the paternalistic treaty and reserve system that First Nations were placed under (although First Nations did not choose paternalism and not all wanted to sign treaties). First Nations also differed with Ottawa in their interpretation of treaties. Saunders noted Metis rejected the protection of the Crown as the price for retaining their ability to be self-governing. Sadly, Ottawa came to forget the self-government part for First Nations and adopted an assimilationist policy. Importantly, Ottawa did not set aside reserves for Metis under treaties, meaning the Metis would unfortunately not be guaranteed a land base as the First Nations.

At one point, the Cree called the Metis “o-tee-paym-soo-wuk,” which means “their own boss.” As one point of distinction, Metis also held property individually, not collectively as First Nations on reserves.

A 2013 document prepared for the Metis National Council on the Daniels ruling stated that the federal government could enact a Canada-Metis Nations Relations Act, which would recognize Metis governance structures, funding for Metis governments, and Metis rights. Unlike the Indian Act (which Ottawa imposed on First Nations), that law would not create a system where the Minister of Aboriginal Affairs controls band councils and reserves.

Ottawa and the provinces can then negotiate with the Metis over land transfers, resource revenue sharing and participation of Metis in resource development projects. Perhaps that is the right place to start.

Joseph Quesnel is an Aboriginal policy analyst who focuses on Aboriginal policy, property rights, and water market issues.

Joseph is a Troy Media contributor. Why aren’t you?

The views, opinions and positions expressed by columnists and contributors are the author’s alone. They do not inherently or expressly reflect the views, opinions and/or positions of our publication.