Melissa Mollen-Dupuis and I don’t know each other but we appear to share similar thoughts on the journalism around Kamloops, B.C. and the discovery of an unmarked grave containing remains of Indigenous children.

Melissa Mollen-Dupuis and I don’t know each other but we appear to share similar thoughts on the journalism around Kamloops, B.C. and the discovery of an unmarked grave containing remains of Indigenous children.

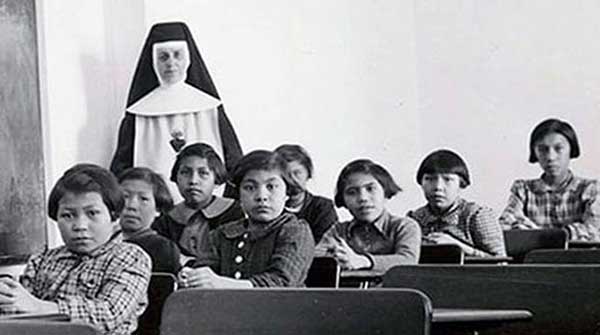

In an interview with Montreal’s Le Devoir newspaper recently, Mollen-Dupuis was sharply critical of media response to the shocking news that ground-penetrating radar has revealed the bones of up to 215 of those children at the site of the former Indian Residential School near the south-central Interior city.

“Why weren’t journalists from the big media outlets in place on Friday? Why weren’t journalists interested a finding the names of the children, in talking to families, and understanding what happened?” demanded the co-organizer of the Indigenous Idle No More movement in Quebec.

I, too, have been wondering why the streets of my old hometown weren’t swarming with journos covering the story even with the logistical hurdles of COVID and the reluctance of the Tk’emlúps te Secwepémc First Nation to comment further on the findings. As Mollen-Dupuis noted in her Le Devoir interview, had so many non-Indigenous bodies been found anywhere in Canadian soil, the swarm would have descended within hours, especially given the international attention the finding has attracted.

Indeed, after overcoming the disbelief that the town where I grew up could be at the centre of such evil, the journalistic part of my brain began buzzing with the myriad of questions that have simply been left hanging. Just for starters, it has been repeatedly reported that the remains of a three-year-old were among those found. How, I wanted to know right from the start, can ground-penetrating radar determine a deceased’s age that precisely – doubly so for a dead child?

| RELATED CONTENT |

| Does the Pope’s apology really mean reconciliation is coming? By Gerry Chidiac |

| Improve Indigenous lives by looking forward By James McCrae |

| Finding a new path forward driven by Indigenous people By Ken Coates |

| We must discover the truth, no matter how horrible By Gerry Chidiac |

A very good follow-up story in the Globe and Mail explains how such radar works. It makes clear that, while not 100 percent reliable, the results are credible provided the instruments are deployed by well-trained, experienced technicians who know how to read the results. But that kind of specificity around age? Without the body being exhumed?

And even if the age determination is accurate, a further critical question arises: What was a three-year-old doing at a residential school for seven to 15-year-olds? Might the gravesite have served the school but also the rest of the First Nation as well? If so, was it a graveyard rather than the original description as a “mass grave”? The difference is obvious, and essential to establish. So far, none of the reporting appears to have even raised the issue.

There are a host of other such unknowns. A number go directly to Mollen-Dupuis’ criticism of media failure to actually go to Kamloops to cover the story. If they did, they would have the opportunity to see the landscape I know as someone who grew up there, who lived there post-university and worked for the local daily newspaper. They could appreciate that the First Nation itself has long been significantly integrated with Kamloops.

It is, after all, right across the South Thompson River, no more than a few kilometres from downtown. When I lived there, non-Indigenous businesses leased land on the First Nation site. People from what was once called the Kamloops Indian Band were neighbours. Len Marchand, who was a graduate of UBC and had a master’s degree in agriculture from the University of Idaho, was the first Status Indigenous MP elected to the House of Commons. He defeated a powerful local lawyer and member of the Diefenbaker cabinet, Davie Fulton. Marchand himself had been at the residential school. So this was no remote, back-of-beyond one-room schoolhouse. People from the First Nation crossed the bridge to shop, to hang out, and to access necessary medical care at the Royal Inland Hospital, which was right next door to the St. Anne’s Catholic School and just up the hill from Sacred Heart Catholic Church.

So how, the question must be asked, was it possible for as many as 215 bodies to be buried without anyone noticing, without anyone raising concerns, without anyone seeing graves being opened and closed? Does the absence of any such awareness suggest the bodies were mainly from the late 19th or early 20th century before Kamloops itself developed substantially? Were they possibly laid in their graves as a result of successive waves of epidemics, meaning large numbers of deaths at one time? We don’t know. And in the initial reporting at least, no one seems to be asking those questions.

To ask such questions in no way seeks to deny, discredit or minimize the finding of the remains. Bodies – Indigenous bodies – have been found, apparently quadruple the number cited by the Truth and Reconciliation Commission in its estimate of 51 deaths at the residential school. Nor does it seek to distract from the racism Indigenous people faced in the place where I grew up. Absolutely there was racism. A memory of a particular grotesque incident I witnessed as a child can still, all these many years later, bring tears of fury to my eyes.

But as the old song says, tears are not enough. Only answers that combine to provoke action ultimately count. What asking those basic journalistic questions does is shine an ever sharper, clearer light on the horrible racist truth of what happened at Canada’s residential schools. It leaves us no excuse, no diversionary intellectual ploy, to evade the truly shameful history of our country’s treatment of our Indigenous peoples.

We have, through our collective history right up to this moment, been abominable in our disregard for their most fundamental human rights, for their fundamental humanity. It is a disgrace upon us; one that only now we are beginning to own up to and seek to amend – far too slowly and grudgingly in my book.

In that sense, and another point on which I agree with Melissa Mollen-Dupuis, the horror from my hometown has at least sent a wake-up shock wave across the country.

“The fact we’re talking about children, and about 215 children, that touches everyone,” she told Le Devoir.

She is absolutely right. Alas, it’s also where the journalistic failings on this story take on such importance. If that “touch” isn’t sustained by cold, hard, factual, contextual reportage, it runs a terrible risk of lapsing back into the facile happy face amnesia that makes many of us feel virtuous just because we start gatherings with the boilerplate acknowledgment that we are on unceded First Nations territory.

That is not reconciliation. Nor is simply attacking the statues of our forebears who made horribly bad political decisions. At best, those constitute cost-free lip service. If the well-reported deaths of children cannot move us beyond that toward real-world deep and, yes, painful change, then we are no longer merely wrestling with our history. We are a country bound for a perilous moral fate. Let there be no question about that.

Peter Stockland is Senior Writer with Cardus, and Editor of Convivium.

Peter is one of our contributors. For interview requests, click here.

This commentary was submitted by Convivium, Cardus‘s online magazine. Cardus is a leading think tank and registered charity. Convivium is a Troy Media Editorial Content Provider Partner.

The views, opinions and positions expressed by columnists and contributors are the authors’ alone. They do not inherently or expressly reflect the views, opinions and/or positions of our publication.

© Troy Media

Troy Media is an editorial content provider to media outlets and its own hosted community news outlets across Canada.