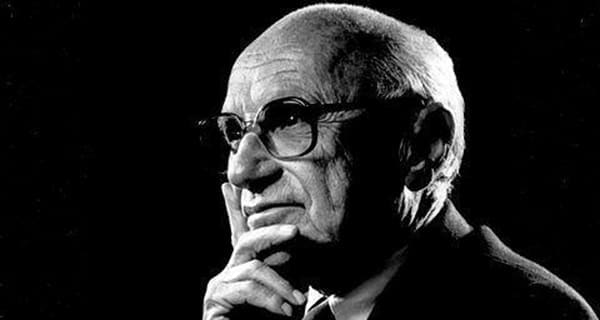

The National Post’s Terence Corcoran is a celebrated champion of free markets. In his latest post, “Milton Friedman is right, profit is a company’s only purpose,” he champions one of the most controversial principles in global capitalism.

The National Post’s Terence Corcoran is a celebrated champion of free markets. In his latest post, “Milton Friedman is right, profit is a company’s only purpose,” he champions one of the most controversial principles in global capitalism.

Corcoran’s primary fear is that “a long list of academics, consultants, business leaders and politicians – many of them Canadian – want to overthrow the idea that a corporation’s primary purpose is to make shareholders money.”

Worse, he quotes Friedman to suggest, “giving social and political responsibilities to business leaders installs unelected corporate managers in positions of unelected power.”

Is he right?

There are two important questions at play in this argument:

- What’s the primary purpose of business?

- Who, if anyone, is responsible for advancing the greater good in society?

As to the first question, let’s face it: in the absence of a financial surplus a business won’t exist. So being profitable in the capitalist system is essential.

The real question is: Does focusing on maximizing returns to shareholders optimize the profit potential of a business?

Consider the fate of one of Corcoran’s example companies, General Motors.

It’s interesting to compare the management priorities of two former chief executive officers of GM, old-school Alfred P. Sloan Jr., GM’s CEO from the 1920s to the late ’50s, and Friedman-enthusiast Roger B. Smith, General Motor’s CEO during the 1980s.

Sloan is famous for raising General Motors to the top rank in reputation, quality and service. Throughout his tenure, General Motors grew consistently and maintained an industry-dominating market share (87 percent at its peak).

However, incredibly, GM’s share price hardly merited a mention in Sloan’s autobiography and, although financial management systems were important, profits took a back seat to production efficiency, divisional structuring and, most importantly, GM’s customers.

Smith is the leader most closely associated with GM’s long-term decline. His priorities are illustrative, for they were the opposite of Sloan’s.

Under Sloan, the company ‘s primary focus was building excellent automobiles; under accountant-trained Smith, GM’s primary focus was maximizing shareholder returns.

According to Smith, standardizing parts and cutting costs across all model lines made perfect accounting sense. But it had the unintended effect of impairing key intangible assets by eliminating the differentials in GM auto brands and decimating the overall quality of the company’s products.

In many ways, Smith’s tenure was the beginning of the end for a great American company.

As to our second question, here Friedman and common sense diverge dangerously.

Friedman’s worldview is rooted in the philosophy of Ayn Rand, who is famous for suggesting that society doesn’t exist. For Rand, individuals have no moral responsibility for one another. Therefore, business leaders assuming larger social responsibilities are in error.

But the truth is that paying attention to other stakeholder interests is not a diversion; it’s management’s job. Building and sustaining good relations with employees, customers, suppliers and the public at large strengthens key intangible assets vital to the health of a business and its continuing relevance to stockholders.

It’s quite common among economists of the Friedman school to proclaim that free markets make free people. The truth is that free people make free markets.

Why?

Because markets don’t self-regulate, people do. A society in liberty, populated by individuals with high levels of social responsibility, exercising good behaviour, can support open markets and let them run free of interference because individuals make good choices.

In the absence of individual self-regulation, markets become corrupted – as is evident today.

The bottom line for Friedman’s principle is: does it work in practice?

The evidence after half a century of monetarism is not good. Many iconic businesses, in the oil industry in particular, are floundering, unable to deliver value due to a growing lack of social reinforcement.

In addition, at the system level, the situation is worse. Environment degradation, particularly in emerging economies, is out of control while capital concentration is growing to dangerous levels.

In addition, the interests of employees, customers and other stakeholders have consistently been submerged by the overwhelming priorities of passive stockholders.

The truth is that a business in not an ethical island. Legally, corporations are artificial individuals with all of the rights, privileges and power of real individuals. Like everyone else, they owe a burden of care to enhance the advance the society in which they operate.

Friedman was wrong and it’s time to reset capitalism on a more sustainable course for the 21st century.

Robert McGarvey is an economic historian and former managing director of Merlin Consulting, a London, U.K.-based consulting firm. Robert’s most recent book is Futuromics: A Guide to Thriving in Capitalism’s Third Wave.

Robert is a Troy Media contributor. Why aren’t you?

For interview requests, click here. You must be a Troy Media Marketplace media subscriber to access our Sourcebook.

The views, opinions and positions expressed by columnists and contributors are the author’s alone. They do not inherently or expressly reflect the views, opinions and/or positions of our publication.