It’s common knowledge that neither Alberta nor Newfoundland found the political courage when the oil patch was awash with cash to create substantive heritage funds.

It’s common knowledge that neither Alberta nor Newfoundland found the political courage when the oil patch was awash with cash to create substantive heritage funds.

While Alberta Premier Peter Lougheed argued persuasively for their need in the 1970s and ’80s, leadership on the issue pretty much ended with his political career. Ever since, Alberta Conservative premiers, from Getty to Redford, talked the talk but basically spent the cash.

In Newfoundland, the same pattern held true, with a series of premiers from Clyde Wells to Danny Williams choosing to spend heavily on government programs and public infrastructure when oil was at its price peak, rather than create sovereign funds for the future.

Meanwhile, Norway has socked away more than $1 trillion.

The debate about the best use of government revenues are well-established in the public mind, but who has been examining the impact of private oil revenue expenditures on the quality of family life? Who is reporting on how dependent Newfoundland’s extended families are on $100,000-plus incomes in the trades? Or how the incomes earned so far have been recycled back into the privately owned infrastructure of family life?

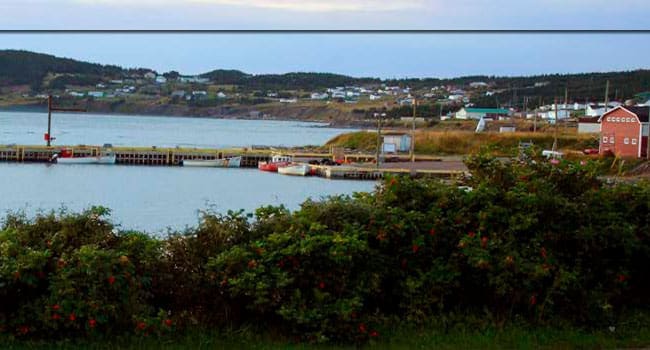

I have just returned from a meeting in Rocky Harbour, a Newfoundland outport adjacent to Gros Morne National Park. The scale of recent family level expenditures there is obvious.

New houses, new cars and trucks, ‘side-by-sides’, quads, large power-boats, and snow machines. A drive through any of the Gros Morne enclave outports (like Rocky Harbour, Cow Head, Curzon, Sally’s Cove, Norris Point, or Woody Point) reveals extensive new wood frame housing construction, closely following the old ‘salt-box,’ or ‘biscuit box’ architecture, only on a larger, more elaborate scale.

Similar expenditures have created a blossoming tourist bed-and-breakfast business culture, catering to global tourists seeking time in Gros Morne National Park. Most Canadians can probably recognize a magnificent photograph of Western Brook Pond, now, even if they don’t know that it isn’t a land-locked fjord, and a lake, not a pond, in mainland landscape terminology.

While the three-month (mid-June to mid-September) tourist season is highly lucrative, it seems a bit of a stretch to conclude that it generates enough revenue to pay for all of the capital improvements that are so broadly evident. Everywhere, you hear references to oilpatch jobs ‘away,’ that result in local tithing and sharing of the oil wealth. It’s got nothing to do with heritage funds, and everything to do with family resources being recycled back home into local consumption on a broad scale.

While there is much evidence of new housing construction and the purchase of high-ticket capital items, one wonders about the aggregate of family savings and investment accounts? Ultimately, that’s not the public’s business, and each family has to fend for itself.

It is evident, however, that the incentive to invest back home is strong, and when the oil price bust began in 2015, many Newfoundlanders headed home to weather the slow-downs and layoffs in Alberta.

Everywhere people were aware of the return dates to Fort McMurray, the looming jobs-boom in post-fire reconstruction, and the need to help out the people who had lost homes, jobs and livelihoods to the fire termed “the beast.” Restaurants on Water Street in St. John’s had professionally designed cards on the tables encouraging a donation to the Red Cross and the rebuilding of Fort McMurray via the restaurant bill. None of the signs that I saw said Fort McMurray, Alberta, either. Nobody needs to be told where it is.

All of this suggests to me that when governments fail to act in conserving resource royalties, families step in to recycle the boom-times cash. While many Albertans may not know it, Rocky Harbour is a major beneficiary of oilsands wealth. Pointedly, Newfoundlanders have chosen to invest it in their community futures.

Mike Robinson has been CEO of three Canadian NGOs: the Arctic Institute of North America, the Glenbow Museum and the Bill Reid Gallery. Mike has chaired the national boards of Friends of the Earth, the David Suzuki Foundation, and the Canadian Parks and Wilderness Society. In 2004, he became a Member of the Order of Canada.

The views, opinions and positions expressed by columnists and contributors are the author’s alone. They do not inherently or expressly reflect the views, opinions and/or positions of our publication.