Saudi Arabia has reminded us once again of the power of the world’s largest oil producer. Through Saudi Aramco, a country with only 35 million people controls 11 percent of global supply.

Saudi Arabia has reminded us once again of the power of the world’s largest oil producer. Through Saudi Aramco, a country with only 35 million people controls 11 percent of global supply.

Saudi Arabia can influence global oil prices simply by adjusting output. It has demonstrated this many times. The Saudis also control OPEC, but don’t advertise it.

In 1973, OPEC cut back production to punish western interference in Middle East politics. That oil embargo and subsequent price spike plunged the world into an economic recession that lasted more than a decade.

When oil prices fall too far, the Saudis cap the downside by reducing output, which supports other producers and helps maintain multiple and diverse oil supplies.

|

| Related Stories |

| Energy-rich Middle East countries smiling all the way to the bank

|

| The coming energy crisis

|

| Global energy security should be a national imperative |

Oil is critical to the Saudi economy. The Saudis would like to sell as much oil as can be produced sustainably at a fair price as long as possible.

A price too low hurts their economy.

A price too high hurts customers and the long-term market.

However, the price that is “just right” remains impossible because of geopolitics and macroeconomics.

On Oct. 4, Aramco CEO Amin Nasser publicly expressed deep concern about current oil markets in a world that seems determined to impair the continued development of a resource society cannot survive without.

Nasser said, “If China were to open up a little we will find our (spare) capacity eroded completely … the world should be worried because this is no cover for any recovery or any unforeseen interruption anywhere in the world.”

Another example is air travel which, by returning to pre-COVID levels, would increase demand by 1.7 million barrels per day.

Aramco has long warned of the dangers of underinvestment in the oil sector, including supply shortages and economic disruption. But discouraging the development of new production is exactly what the western world has been doing because of concerns about climate and decarbonization.

After the COVID-19 pandemic lockdowns of early 2020, oil demand and prices collapsed. OPEC morphed into OPEC+ by cooperating with Russia to control output. When OPEC+ shut in 10 million barrels a day, it stabilized prices and protected producers in Canada, the U.S. and around the world from financial collapse.

At that time, having Saudi Arabia and Russia – hardly paragons of democracy or human rights – in control of 20 percent of the world’s oil supply didn’t bother anybody.

After all, fossil fuels were a sunset industry.

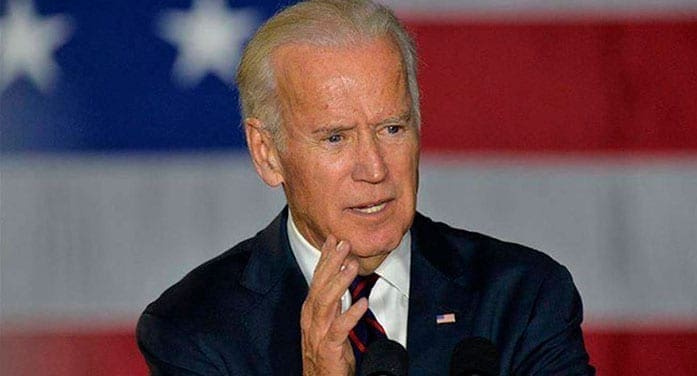

In early 2021, Joe Biden was sworn in as U.S. president. So began contradictory and unpredictable changes in U.S. energy policy that now reinforce Aramco’s warning because nobody knows what the White House will do next.

First, Biden cancelled the Keystone XL pipeline, which helped cap growth in Canada’s massive oil sands resource. His decision was part of the anti-fossil fuel platform that helped the Democrats win the 2020 election.

But as oil prices began rising in mid-2021, Biden looked offshore for more oil to keep U.S. prices down. At a G20 meeting in November on his way to the COP26 climate conference in Glasgow, Biden called on Saudi Arabia to increase output, an odd favour to ask from a U.S. president who, while on the campaign trail a year earlier, had called Saudi Arabia a “pariah state.”

Then the White House extended an olive branch to Iran, currently under siege internally and externally for its oppressive treatment of women. The U.S. would remove its economic sanctions obstructing Iranian oil exports if that country recommitted to restricting its nuclear development activities.

Biden’s rapprochement with Iran disappointed Saudi Arabia, which has been in a political and religious power struggle with Iran in the Persian Gulf for decades.

Then came the Russian invasion of Ukraine in February. The U.S. responded by punishing Russia in every way except by committing American troops and aircraft. America has supplied weapons and money, introduced economic sanctions on Russia, and is leading a G7 attempt to cap Russian oil prices to further starve Russia for cash.

To lower gasoline prices before the November mid-elections, Washington decided to compete with OPEC+ and U.S. producers by releasing one million barrels per day from America’s Strategic Petroleum Reserve, which suppressed prices and sent the wrong signal to producers, which would ramp up spending if prices kept rising. The U.S. rig count declined slightly in September after rising steadily for two years.

Monetary policy to tame inflation has caused the U.S. dollar to strengthen, thus reducing headline oil prices. Uncertainty about a recession’s impact on oil demand has also capped prices.

On Oct. 5, OPEC+ expressed its displeasure with Biden’s decisions by cutting output by two million barrels per day. Saudi Arabia even chose to side with new “pariah state” Russia instead of its former ally America, a relationship that dates back to the Second World War.

As producers develop their 2023 budgets, no big capital increases are planned. Why? Because the mixed messages have created tremendous uncertainty.

Those that should be drilling will be very cautious until Washington and Ottawa signal they want more petroleum, not more politics. Western companies don’t, and will never, take direction from OPEC+.

The world should be worried. Higher oil prices are assured.

David Yager is an oilfield service executive, oil and gas writer, and energy policy analyst. He is author of From Miracle to Menace – Alberta, A Carbon Story.

For interview requests, click here.

The opinions expressed by our columnists and contributors are theirs alone and do not inherently or expressly reflect the views of our publication.

© Troy Media

Troy Media is an editorial content provider to media outlets and its own hosted community news outlets across Canada.