The Public Health Agency of Canada study’s conclusions are a fantasy, quite divorced from reality

By John Hardie

David Vickers

Stefan Eberspaecher

Claudia Chaufan

and Steven Pelech

Rather than learning from the painful lessons of the past three years, it’s obvious that we’ve entered a post-pandemic phase of government-led alarmism.

John Hardie |

David Vickers |

Stefan Eberspaecher |

Claudia Chaufan |

Steven Pelech |

The Public Health Agency of Canada (PHAC) – including Theresa Tam – has published a study in a Canadian public health journal declaring that pandemic-inspired restrictions substantially reduced the impact of COVID-19 in Canada. Counterfactuals of effects of vaccination and public health measures on COVID-19 cases in Canada: What could have happened? asks us to believe an imagined story about what may have happened had Canada’s public health measures not been implemented.

|

| Related Stories |

| Study: COVID-19 was more bark than bite

|

| Post-secondary COVID-19 policies in Canada must end

|

| COVID mismanagement needs to be examined by an independent panel

|

However, the result is a counterfactual narrative of a fantasized Canada quite divorced from reality.

Recent debate on the study’s findings has made it evident that Theresa Tam and her collaborators (“the authors”) are victims of common modelling pitfalls that have stripped their objectivity and, accordingly, affected the quality of their model and its output.

Instead of relying on modelling forecasts, the authors resort to “back-casting” to state “what may have happened” or “what could have been” had governments not acted on our behalf.

However, giving credence to such questionable results occurs all too often when sensational outcomes are observed. Unfortunately for any modelling study, the historical path – the one involving no interventions – was foreclosed the moment pandemic responses began. Neither the authors, nor anyone else, can ever observe the simultaneous response and non-response of Canada’s experience with COVID-19.

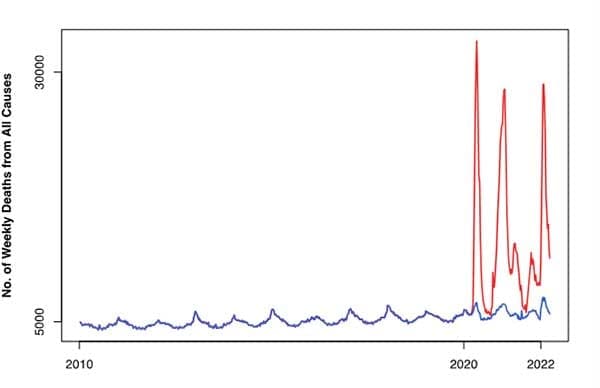

Their most-dramatic claim is that, without social restrictions and vaccines, up to 800,000 COVID-19-related deaths could have occurred. The figure below shows 12 years of all-cause mortality data in Canada (blue line), with the authors’ “worst case” superimposed (red line).

For us, two things make the authors’ assertion incompatible with any reasonable view: one, there was no obvious increase in all-cause mortality between 2020 and 21 that exceeded historical trends (blue line), and two, the death count of “up to 800,000 people” (red line) surpasses the number of Canadians killed in the 1918 influenza pandemic and two World Wars – combined. It begs the question: could an infection with a survival rate >99 percent really have been the single-most devastating health event in a century? The reader can decide if they find these results plausible, or fantastic.

All models are unrealistic to a degree (although this is not a “fatal flaw”). However, models are only as good as the assumptions upon which they are based. Unfortunately, the authors have hung their results on assumptions that underestimate the acquisition, extent, and durability of natural immunity and that very likely overestimate early viral spread and the duration of vaccine-acquired immunity.

The authors also assume that the spread of infection dropped consistently with the stringency of closures and other social restrictions: when strict, transmission was low; when relaxed, transmission increased. However, there is evidence that these measures didn’t work “as advertised.” In many provinces, their effect may have plateaued by April 2020. Stricter measures did not translate into a proportionately slower spread.

Unfortunately, this didn’t stop the authors from forcing their model to respond as if they had. In their “worst case” scenario, large amounts of infection and disease are – conveniently – a foregone conclusion unless they get flattened by top-down government actions. The agency of Canadians and its bottom-up influences on transmission, such as people’s natural tendency to avoid contagion, are never considered.

Their least-subtle omission was the failure to disclose conflicts of interest. While PHAC scientists might claim they only provide guidance on sub-national pandemic responses, the interests of many federal health-related agencies are certainly evident.

For example, the federal government’s purchase of COVID-19 vaccines preceded their approval by Health Canada, and some of the most restrictive measures imposed on Canadians (such as vaccine requirements for commercial travel) came from the federal level. As it happens, four of the authors are also directly employed by the federal government. The study’s authors can hardly be viewed as not having competing interests in favourably evaluating pandemic policies.

All this leads us to wonder: was their article a genuine evidence-based analysis of government policies? Or, rather, a blatant attempt to justify these policies? To their credit, the authors admit that Canada’s response to the pandemic was imperfect and any unintended consequences need to be investigated. It will truly be a measure of the honesty and integrity of PHAC and their provincial partners if the latter is ever realized.

Dr. John Hardie is the former head of Dentistry at Ottawa Civic Hospital and Vancouver General Hospital. Dr. David Vickers is a Statistical Associate and Epidemiologist with the Centre for Health Informatics at the University of Calgary’s Cumming School of Medicine. Dr. Stefan Eberspaecher is a Doctor of Chiropractic with experience in clinical research and delivery of evidence-based healthcare in low- and middle-income countries. Dr. Claudia Chaufan is a Professor of Health Policy and Global Health at York University. Dr. Steven Pelech is a Professor in the Department of Medicine at the University of British Columbia.

For interview requests, click here.

The opinions expressed by our columnists and contributors are theirs alone and do not inherently or expressly reflect the views of our publication.

© Troy Media

Troy Media is an editorial content provider to media outlets and its own hosted community news outlets across Canada.