Extending over 14 acres, La Recoleta is a famous cemetery in Buenos Aires, Argentina. A 2013 CNN travel piece called it one of the world’s 10 most beautiful.

Extending over 14 acres, La Recoleta is a famous cemetery in Buenos Aires, Argentina. A 2013 CNN travel piece called it one of the world’s 10 most beautiful.

Today’s layout dates from the early 19th century and is said to resemble “a city more than a burial ground with its impressive neo-classical gates opening up to winding tree-lined streets.”

The most notable of La Recoleta’s approximately 4,700 above-ground vaults is the black marble mausoleum serving as the final resting place of Eva Peron. Or, to use her popular sobriquet, it’s the burial place of Evita.

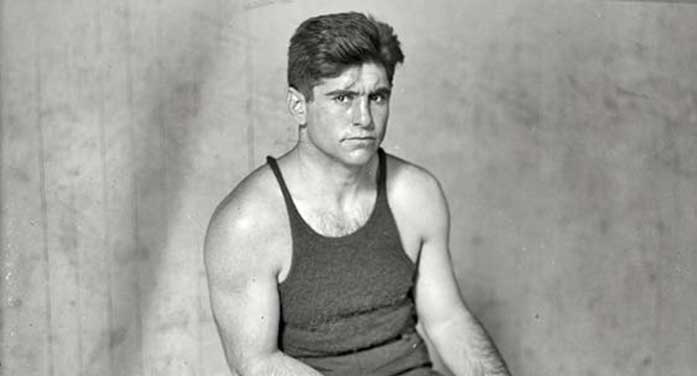

Although less imposing than Evita’s, there’s another mausoleum belonging to a figure who was also once famous beyond Argentina’s boundaries. Guarded by a full-sized bronze statue standing at its entrance, the vault contains the earthly remains of heavyweight boxer Luis Angel Firpo.

Firpo – dubbed the Wild Bull of the Pampas by American journalist Damon Runyon – was one of the two participants in what the New York Times contemporarily described as “the greatest fight in the history of pugilism.” The other participant was the fearsome Jack Dempsey.

The son of an Italian labourer, Firpo was born in Junin, Argentina, in 1894 and started boxing professionally in 1917. For the first several years he fought only in South America before broadening his horizon in 1922. The heavyweight championship of the world was where the real money was, and that meant competing in the United States.

Firpo wasn’t particularly large by today’s heavyweight standards, but he was relatively big in terms of the 1920s norm. Standing a smidge over six foot two and weighing in at 215 pounds, he cut an impressive figure. You might even call it intimidating.

And defensive subtlety wasn’t his style. He was all about aggression and clubbing his opponents into submission. It made him a colourful crowd-pleaser. There’d be lots of action when he was in the ring.

On Sept. 14, 1923, he squared up to Dempsey at New York’s Polo Grounds before a crowd estimated at 85,000 to 90,000. With Dempsey’s world title at stake, the fight produced the second million-dollar gate in boxing history. It was a huge sum at the time.

While the contest didn’t last long, excitement trumped brevity. Several minutes of unmitigated mayhem would be an apt description.

The first round was a frenzied affair. After being floored no less than seven times, Firpo knocked Dempsey through the ropes and onto the reporters sitting at ringside. One account described Dempsey as disappearing “as though a trapdoor had opened and swallowed him.”

But assisted by a helpful push from representatives of the New York Tribune and Western Union, Dempsey managed to scramble back with just a second to spare. Thus restored to his feet, he dispatched Firpo in the next round.

Gene Tunney – the man who dethroned Dempsey three years later – was at the fight and thought Firpo unlucky. Sure, Dempsey was “by far the better fighter that day,” but Firpo’s refusal to engage a manager cost him.

Tunney’s assessment had two points.

First, the fact that Dempsey was actually out of the ring for more than 10 seconds would’ve led a savvy manager to be “in there, raising Firpo’s hand and claiming the championship.”

And second, a manager would’ve intervened with the referee when Dempsey repeatedly hovered over the fallen Firpo, “clubbing him down again each time he got up.”

Firpo fought another dozen times after Dempsey, only losing once. He finished his career with 31 wins (26 by knockout) and just four losses.

Firpo fought another dozen times after Dempsey, only losing once. He finished his career with 31 wins (26 by knockout) and just four losses.

But unlike many ex-fighters, Firpo didn’t fade into a penniless old age. Not by a long shot.

Back home in Argentina, he became a large-scale rancher, running an estimated 8,000 cattle, 4,000 sheep and 400 horses. And he was very much a hands-on businessman, carrying a pen “that he is constantly whipping out and using to figure everything down to the last cent.”

Tunney told an anecdote about visiting Firpo on his Argentinian estate in the mid-1950s.

“Luis,” Tunney said, “they tell me you’re worth $10 million today.”

“Oh, no,” Firpo demurred. “Not 10. No. Maybe only five.”

That would be north of $50 million in today’s money. The Wild Bull of the Pampas was nobody’s fool.

Pat Murphy casts a history buff’s eye at the goings-on in our world. Never cynical – well, perhaps a little bit. For interview requests, click here.

The opinions expressed by our columnists and contributors are theirs alone and do not inherently or expressly reflect the views of our publication.

© Troy Media

Troy Media is an editorial content provider to media outlets and its own hosted community news outlets across Canada.