Only when the truth is known can an honourable reconciliation be forged

On Jan. 31, Dr. Michael Mahon, president of the University of Lethbridge, cancelled a talk that Dr. Frances Widdowson was scheduled to present. Like all scholars, Dr. Widdowson has nuanced views on many issues, and she was going to speak on “How Wok-ism Threatens Academic Freedom.”

On Jan. 31, Dr. Michael Mahon, president of the University of Lethbridge, cancelled a talk that Dr. Frances Widdowson was scheduled to present. Like all scholars, Dr. Widdowson has nuanced views on many issues, and she was going to speak on “How Wok-ism Threatens Academic Freedom.”

Even though Mahon had not heard her argument, he nevertheless explained why he cancelled the talk: “We are committed to the calls to action of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) of Canada. It is clear that the harm associated with this talk is an impediment to meaningful reconciliation.”

Given the title of Dr. Widdowson’s talk, this response is not logical. Unfortunately, in Mahon’s mind, reconciliation between indigenous people and other Canadians depends on two conditions:

1) agreeing with all 94 calls to action in the TRC report; and

2) stopping people who may disagree from expressing their opinions, at least on his campus.

|

| Related Stories |

| The genocide lie about residential schools

|

| House of Commons finally describes residential schools as genocide

|

| We must accept the mistakes of the past and make them right

|

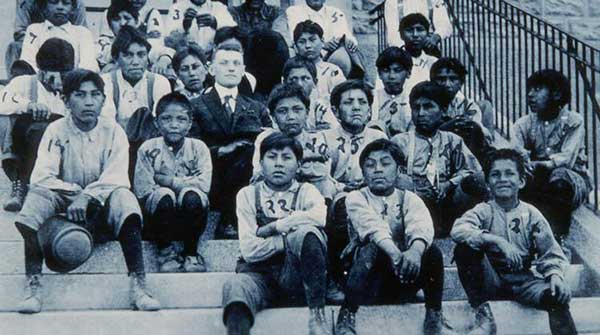

Rather than discourage civil discourse, Canadian universities and the churches, especially those that managed Indian Residential Schools (IRS), should welcome debate about the TRC report and its 94 calls to action. These calls are, without exception, demands that have serious financial and social implications for universities, churches, and, indeed, all Canadians.

In a democracy, respectful disagreement and debate must be preserved, if not enhanced. Debate on important policy issues is fundamental to our way of life.

About 20 Canadians – including Frances Widdowson – have been called “residential school deniers” simply because they ask for evidence beyond what some survivors claim. Of course, I prefer the describe them as “historical realists”.

The realists began questioning the official narrative when “215 children’s bodies were discovered” by ground penetrating radar (GPR) in the Kamloops Indian Residential School yard. One of the realists examined the historical records and discovered that, in the mid-1920s, clay pipes for a septic field were buried in the surveyed area.

As a result, the realists wondered if the GPR had rediscovered the clay pipes and not the graves of IRS students. To date, Tkʼemlúps te Secwépemc (formerly the Kamloops Indian Band) has not released the GPR report, and it has not allowed excavations to see what the GPR had picked up.

Surprisingly, none of the 94 calls to action demand that schoolyards should be searched for the bodies of murdered and buried IRS children. This is important because the commission worked for six years, spent over $60 million, and did not report credible evidence that children had been murdered and buried in residential schools.

The commissioners did, however, hear one horrifying story from an IRS survivor, Doris Young, who testified that she witnessed the murder of a young child at the Anglican Elkhorn Indian Residential School in Manitoba.

Strangely, the commissioners never referred her testimony to the proper authorities to be thoroughly investigated and never asked other survivors if they saw children being murdered and buried in residential school yards. Even more surprising, the TRC commissioners never called for residential schoolyards to be searched for possible graves of indigenous students.

Since the Kamloops “discovery,” there have been hundreds, if not thousands, of claims of potential graves in residential schoolyards across Canada. These claims must be as eye-opening to the commissioners as they are to other Canadians.

As the commissioners know, there are cemeteries close to many residential schools for a simple reason. Residential school chapels often served as churches for local parishioners, both indigenous and non-indigenous, and as expected, parish cemeteries were located close by.

In many cases, the wooden crosses used to mark graves have deteriorated. It is important to note that using headstones is a Christian practice many indigenous people never fully adopted. So even today, many graves in reserve cemeteries are unmarked.

Nevertheless, Mahon ruled that realists like Frances Widdowson should not talk about wokism because it may touch on indigenous topics. Some people may be offended, jeopardizing reconciliation – as if reconciliation is so fragile that one person’s views could destroy the whole project.

But to arrive at the truth, which according to the TRC is necessary for reconciliation, Canada needs more discussion, not less, about residential schools and whether or not children were murdered and buried in the schoolyards, even if it makes some people uncomfortable.

The truth must be ferreted out so that justice is served. When the truth is known, an honourable reconciliation can be forged.

Rodney Clifton is a Senior Fellow at Frontier Centre For Public Policy.

For interview requests, click here.

The opinions expressed by our columnists and contributors are theirs alone and do not inherently or expressly reflect the views of our publication.

© Troy Media

Troy Media is an editorial content provider to media outlets and its own hosted community news outlets across Canada.