Bing Crosby’s Silent Night is one of the best-selling records of all time

Silent Night, probably the most famous Christmas carol of all, will be over 200 years old this Christmas Eve.

Silent Night, probably the most famous Christmas carol of all, will be over 200 years old this Christmas Eve.

It was first performed at the parish church in the Austrian village of Oberndorf during midnight mass on Dec. 24, 1818. And, fittingly, the performers included the two men who’d written it.

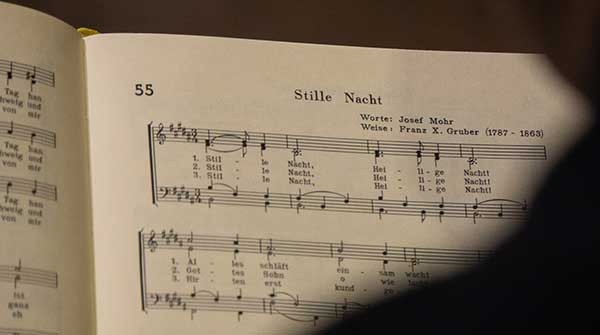

The words had come a couple of years earlier from Father Joseph Mohr’s six-stanza poem Stille Nacht! Hellige Nacht! But it was when he asked his friend Franz Gruber to put it to music in 1818 that a cultural phenomenon was born.

To get a sense of the phenomenon’s size and pervasiveness, consider these few facts:

- more than 26,000 renditions of Silent Night have been recorded;

- it’s been translated into hundreds of languages;

- and the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) has designated it as an intangible cultural heritage.

|

| Related Stories |

| Teaching kids gratitude at Christmas

|

| How to make this Christmas a merry and memorable one!

|

| Balancing fun and professionalism at the Christmas office party |

For most of us, the familiar version dates from the mid-19th century English translation by John Freeman Young, an American Episcopal priest who went on to become bishop of Florida. In addition to theology, Young’s passions included church architecture and translating hymns into English. Silent Night first appeared in his Carols for Christmas Tide (1859).

With so many recorded renditions to choose from, only a fool would try to select a universally definitive interpretation. However, any shortlist of contenders will probably include Bing Crosby’s rendering.

Indeed, compilers of lists regularly name Crosby’s Silent Night as one of the best-selling records of all time. For instance, Wikipedia places it as the third best seller with a cumulative sale of 30 million copies (since 1935). And while it would be imprudent to bet your pension on the accuracy of numbers that date back so far, it’s safe to say that, in one form or another, very large quantities have been sold.

Crosby was reluctant to record the song. Or, for that matter, to record any other religious piece.

Although he was a prodigious carouser, gambler and extramarital dabbler, Crosby remained an early 20th-century Irish-American Catholic at heart. There were certain pieties to be observed and making commercial recordings of religious music would violate propriety. It would be, he said, “like cashing in on the church or the Bible.”

Eventually, though, he was persuaded. He would do it to raise money for the St. Columban Foreign Missionary Society, which was seeking to spread the gospel and do good works in China. Silent Night and Adeste Fideles were thus recorded in 1935.

But as things transpired, the priest spearheading the effort was killed in an automobile accident and the Japanese invasion of China cut off contact with the mission. So instead of China, the royalties went to various charities in the United States and overseas.

Crosby revisited Silent Night and Adeste Fideles in 1942. In fact, if you have a classic Crosby Christmas album in your collection, chances are its recordings of the two songs are from that later session. And listened to now – whether from 1935 or 1942 – they project a quaint, nostalgic sensibility.

Still, however primitive they may sound to the modern ear, they have a characteristic often absent from modern recordings. Rather than being carefully contrived edits, they’re complete performances from beginning to end.

Prior to the post-war introduction of magnetic tape, recording was done directly onto wax. If you didn’t get it right, you had to persist until you did. Clever sound engineers couldn’t fix your mistakes.

Silent Night has also been described as “the Christmas song that stopped World War I,” in reference to the Christmas truce that broke out in parts of the Western Front in December 1914.

Stanley Weintraub, the author of a 2001 book on the subject, ascribes one of the truce’s beginnings to a German officer named Walter Kirchhoff. A tenor with the Berlin Opera in civilian life, Kirchhoff “came forward and sang Silent Night in German, and then in English. In the clear, cold night of Christmas Eve, his voice carried very far.”

What followed was a bizarre hiatus where opposing troops exchanged makeshift gifts, drank beer and even, so the story goes, played football. John Ferguson of the Seaforth Highlanders later reminisced about “laughing and chatting to men whom only a few hours before we were trying to kill.”

Then the war resumed on Dec. 26, continuing until Nov. 11, 1918.

Pat Murphy casts a history buff’s eye at the goings-on in our world. Never cynical – well perhaps a little bit.

For interview requests, click here.

The opinions expressed by our columnists and contributors are theirs alone and do not inherently or expressly reflect the views of our publication.

© Troy Media

Troy Media is an editorial content provider to media outlets and its own hosted community news outlets across Canada.