If you were a child in the 1950s, the chances are that Davy Crockett was briefly a part of your life. On December 15, 1954, the ABC television network broadcast the first episode of a new Disney mini-series loosely based on his exploits, two more episodes followed in January and February 1955, and a concluding two were screened in November and December. In the process, the Crockett craze zoomed into the stratosphere.

If you were a child in the 1950s, the chances are that Davy Crockett was briefly a part of your life. On December 15, 1954, the ABC television network broadcast the first episode of a new Disney mini-series loosely based on his exploits, two more episodes followed in January and February 1955, and a concluding two were screened in November and December. In the process, the Crockett craze zoomed into the stratosphere.

Despite being purportedly surprised at the scope of the popular reaction, Disney quickly introduced an array of licenced products to cash in on the phenomenon. Screen cowboys like Gene Autry and Roy Rogers may have previously dominated the children’s paraphernalia market, but now it was Davy Crockett’s turn.

Indeed, the ubiquity of the coonskin cap became such that one even turned up on a boy who lived two doors down from me in suburban Dublin, thousands of miles and an ocean away from the reach of American TV.

But that wasn’t all. On the marketing principle that no opportunity should be left unexploited, Disney repackaged the TV episodes into two theatrical movies, which then played around the world. In Britain, the first movie – Davy Crockett, King of the Wild Frontier – was one of the year’s highest grossers.

And there was also the music. Even if you never watched TV or went to the movies, the fact that the theme song was all over the radio made it difficult to remain oblivious. Relentlessly catchy, it generated no fewer than three major hit versions, one of which outsold every other record in America for five consecutive weeks.

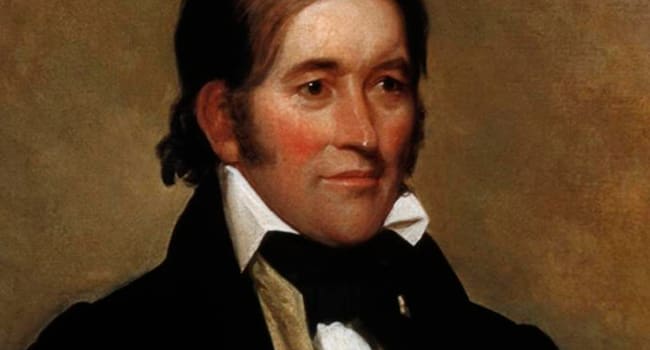

As for authenticity, the Disney version’s narrative outline was historically grounded. Born in Tennessee in 1786, the real Davy Crockett did fight in the early 19th century Indian Wars, did serve three terms in Congress, and did die at the Alamo on March 6, 1836. To be sure, they invented stuff and repeated tall tales, but there was an element of underlying truth to the whole thing.

Of course, historical truth is often a matter of perspective. If you’re American, the Alamo is – or at least was – an inspirational example of fighting for freedom. But if you’re Mexican, you’ll probably see it as part of an episode that culminated in the unfortunate loss of your imperial inheritance.

When Mexico became independent from Spain in 1821, it inherited vast, sparsely settled areas north of the Rio Grande, one of which was Texas. However, holding on to this territory was a major challenge. On the one hand, there were Americans anxious to expand into the largely empty space. And on the other, existing Spanish settlements were perpetually at risk from Indian, primarily Comanche, raids.

Mexico City then had a bright idea. The borders would be opened to American immigration and the new settlers would become loyal Mexicans, while also providing a counterforce bulwark against the Comanche. Conceptually, it may have seemed like a master move, but it didn’t play out that way. Instead, the American settlers revolted in 1835, Texas became an independent republic in 1836, and subsequently joined the United States in 1845. Along the way, the Siege of the Alamo passed into legend.

Mind you, Crockett’s presence at the Alamo was down to his life having taken a wrong turn. Defeated for re-election and politically washed-up, he headed for Texas to make a fresh start at the age of 49. And being the sort of guy he was, volunteering for the fight just came naturally.

Cynicism aside, though, you could say that it was a shrewd career move, albeit one that Crockett didn’t live to personally savour. With its stirring story of a vastly outnumbered force holding off a superior attacker for 13 days, the Alamo is the kind of heroic narrative that begs for dramatization, and the fact that virtually none of the defenders survived bestows an additional aura of martyrdom.

Indeed, a martyred hero is precisely what Crockett became. Although historians argue as to whether he died in the fighting or was summarily executed immediately afterwards, the 1950s Disney version – Davy on the ramparts swinging his empty rifle as Mexican bayonets close-in for the kill – transmitted a powerfully iconic image.

To borrow a phrase from another mid-20th century American movie, “When the legend becomes fact, print the legend.”

Pat Murphy casts a history buff’s eye at the goings-on in our world. Never cynical – well perhaps a little bit.

The views, opinions and positions expressed by columnists and contributors are the author’s alone. They do not inherently or expressly reflect the views, opinions and/or positions of our publication.