It was 100 years ago this May that two diplomats – Britain’s Sir Mark Sykes and France’s Francois Georges-Picot – concluded a secret agreement dividing the (prospective) post-war Middle East into British and French spheres of influence. And by virtue of ignoring local demographic realities, their agreement has been blamed for many of the region’s subsequent woes.

It was 100 years ago this May that two diplomats – Britain’s Sir Mark Sykes and France’s Francois Georges-Picot – concluded a secret agreement dividing the (prospective) post-war Middle East into British and French spheres of influence. And by virtue of ignoring local demographic realities, their agreement has been blamed for many of the region’s subsequent woes.

However, this is something of a bum rap. Whether it’s being attacked from the perspective of motivation or long-term implications, beating-up on Sykes-Picot is silly.

Stripped to its essence, the First World War was a conflict between empires – the British, French and Russian empires on one side and the German, Austro-Hungarian and Ottoman (Turkish) empires on the other. So diplomats tasked with thinking ahead to a post-war settlement would naturally look at it from an imperial perspective and put the national interest of their own countries front and centre. In an imperial age, what else would anyone expect them to do?

The Ottomans, after all, had cast their lot with the Germans and Austro-Hungarians. If they lost the war, their empire would naturally be forfeited. And the victorious powers would expect something for their efforts.

| MORE IN BOOKS |

| 19th century Scottish novelists cast a long shadow By Pat Murphy |

| Robert Conquest, the man who was right By Pat Murphy |

| Canada’s Fenian years featured some interesting personalities By Pat Murphy |

In addition, there’s the fact that Sykes-Picot was only one of the streams contributing to the ultimate settlement. As historian Sean McMeekin puts it, “The partition of the Ottoman empire was not settled bilaterally by two British and French diplomats in 1916, but rather at a multinational conference in Lausanne, Switzerland, in 1923.”

Going further, McMeekin notes that “None of the most notorious post-Ottoman borders – those separating Palestine from Jordan, or Syria from Iraq, or Iraq from Kuwait – were drawn by Sykes and Picot.”

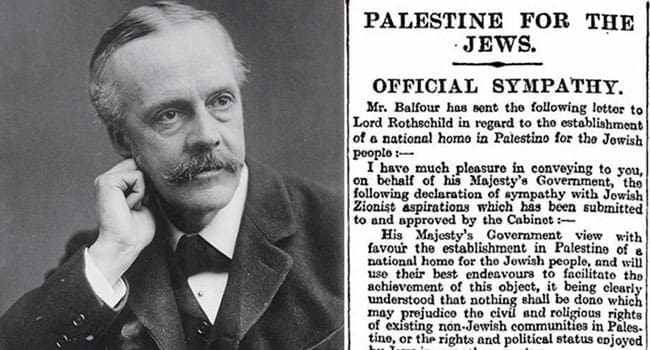

Indeed, the British themselves weren’t exclusively wedded to the agreement, having floated at least two other enticements pertaining to the post-war dispensation. One was the correspondence between Sir Henry McMahon and Hussein, the sharif of Mecca, in which Hussein was allowed to expect an extensive independent Arab kingdom in return for a revolt against the Ottomans. And the other was the Balfour Declaration in support of a Jewish homeland in Palestine.

Of course, these two expedients were in conflict with each other. And in the telling of another historian, Margaret Macmillan, they also “sat uneasily” with the Sykes-Picot scenario, thus underlining how “Promissory notes given in wartime are not always easy to collect in peace.” As ever, caveat emptor should be the watchword of the wise!

But if scapegoating Sykes-Picot is a fool’s errand, there’s no gainsaying the fact that the Ottoman demise radically changed the map of the region. A mere 30 years after the war’s end and 25 years after Lausanne, no fewer than seven new countries had emerged, all of them created out of the Ottoman ruins.

First up, in 1923, was the freshly minted Republic of Turkey, now radically reduced in size from the old empire that had ruled for centuries from Constantinople. Then modern Saudi Arabia was founded in 1932, the same year that Iraq graduated from formal British League of Nations mandate control. Finally, the 1940s brought independence to Lebanon, Syria and Jordan, while also witnessing the foundation of Israel.

In the 2009 edition of his A Peace to End All Peace, David Fromkin observes that some of these new states have a legitimacy problem. Internally, it’s a matter of the regime not being accepted by various religiously/tribally defined population subsets. Externally, it’s a question of either border disputes or – as in the case with Israel and some of its neighbours – a refusal to concede the state’s right to exist.

Still, even if they’d been so inclined, it’s difficult to see how those tasked with determining the post-Ottoman world could have produced a significantly more robust solution.

They could, of course, have retained the empire’s geographic integrity, which would mean the Middle East would now be ruled from Ankara.

Or they could have tried the kind of Pan-Arab arrangement preferred by Hussein of Mecca, which would have placed what’s now Saudi Arabia in the regional driver’s seat.

Or they could have attempted to come up with a territorial design that navigated the various geographically intermingled religious/tribal fissures.

Seriously, though, does anyone really consider any of these alternatives viable? Sometimes merely asking the question is to answer it.

Pat Murphy casts a history buff’s eye at the goings-on in our world. Never cynical – well perhaps a little bit.

For interview requests, click here.

The opinions expressed by our columnists and contributors are theirs alone and do not inherently or expressly reflect the views of our publication.

© Troy Media

Troy Media is an editorial content provider to media outlets and its own hosted community news outlets across Canada.