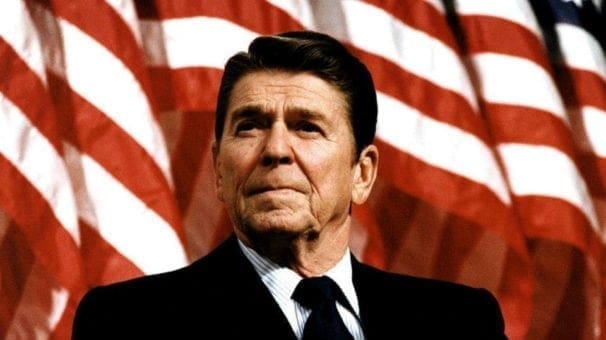

Late in his presidency, Ronald Reagan went to Moscow for a visit that generated some dramatic images and memorable moments. If you’d predicted this when he was elected in 1980, most people – pundits and experts especially – would’ve scoffed at you.

Late in his presidency, Ronald Reagan went to Moscow for a visit that generated some dramatic images and memorable moments. If you’d predicted this when he was elected in 1980, most people – pundits and experts especially – would’ve scoffed at you.

Reagan, so the narrative went, was a dangerous cowboy, a warmonger and a dunce. The best to be hoped for was to try to survive his presidency without the world being blown up. And the idea that he might play a significant role in ending the Cold War was preposterous.

There are several reasons for such a spectacular prognosticating failure, two of which relate to a misreading of who Reagan actually was.

Taking cues from Reagan’s vigorous anti-communism, most commentators fell for a caricature depicting the American president as trigger-happy and itching for a fight. Completely missing was the fact that Reagan had a particular loathing for nuclear weapons and considered conventional thinking on the subject – the doctrine of mutual assured destruction – to be immoral.

Similarly, Reagan’s notorious inattention to most detail obscured the fact that, when engaged, he could be “a surprisingly deft negotiator.” Indeed, his history in that regard was something Reagan took pride in, going all the way back to his days as a Hollywood union leader for the Screen Actors Guild.

A Russian note taker who observed Reagan closely during his negotiations with Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev likened him to “an old lion, lazily watching an antelope on the horizon, taking no interest, dozing a bit. He doesn’t move when the antelope stops only 10 feet away, that’s too far. At eight feet, the lion suddenly comes to life! Reagan the negotiator suddenly fills the room.”

En route to Moscow, the Reagans stopped in Helsinki for four days of rest. At 77-years-old, Reagan tired very easily and experienced great difficulty with jet lag. Then, suitably replenished, they flew to Moscow, touching down on May 29, 1988.

The formal highlight of the agenda was the signing of the instruments of ratification for the Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces (INF) Treaty. To quote historian Robert Service: “The unimaginable had suddenly happened. America and the Soviet Union had not just agreed to limit the number of nuclear weapons they held, they were going to eliminate an entire category of ballistic missiles.”

But there was other business.

Reagan wanted to push the Soviets on the treatment of dissidents while boosting Gorbachev’s internal status. In the American estimation, not everyone in the Soviet power structure was on board with Gorbachev’s perestroika, so it would be appropriate to give him a hand.

Things didn’t initially go well with respect to the dissidents.

A Russian Jewish couple, Tatyana and Yuri Ziman, were having difficulty getting exit visas and their situation was brought to Nancy Reagan’s attention by a family friend. So the Reagans planned to make a symbolic visit to their apartment. In fact, it would be the first stop after arriving in Moscow, preceding even the official welcoming ceremony in the Kremlin.

Unsurprisingly, this didn’t sit well with Gorbachev and the plan was cancelled on the tacit understanding that the Zimans would get their visas. They did several months later but only after Reagan personally followed up with the Soviet ambassador in Washington.

Then, speaking in front of a Vladimir Lenin bust at Moscow State University on May 31, Reagan set out to thread the needle.

He talked about the information revolution and the tiny silicon chip, which “has more computing power than a roomful of old-style computers.” This, he said, “will fundamentally alter our world … and reshape our lives.” But, he added, in order to create and enjoy such things, you needed an open society.

He quoted the Russian writer Boris Pasternak. And he alluded to the famous scene in Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid where the protagonists had to jump to survive, likening it to the need to take a risk with perestroika.

To paraphrase Bret Baier and Catherine Whitney’s new book Three Days in Moscow, he seduced rather than shouted, inspired rather than preached, and respected rather than admonished. Even the habitually unfriendly New York Times characterized it as his “finest oratorical hour.”

Earlier that day, Reagan had responded to a question as to whether he still thought of the Soviet Union as “an evil empire.”

“No,” he said, “that was another time, another era.”

Pat Murphy casts a history buff’s eye at the goings-on in our world. Never cynical – well, perhaps just a little bit.

The views, opinions and positions expressed by columnists and contributors are the author’s alone. They do not inherently or expressly reflect the views, opinions and/or positions of our publication.