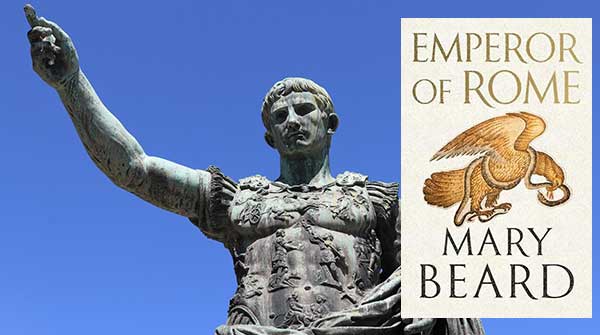

Mary Beard’s latest book, Emperor of Rome, reveals the intriguing world of emperors and power

If ancient Rome tickles your historical fancy, Mary Beard’s recent book might be worth your while. Beard is an English historian generally acknowledged as an authority on the subject, and Emperor of Rome is her latest offering. As she tells the story, being emperor was challenging – and sometimes dangerous – work.

If ancient Rome tickles your historical fancy, Mary Beard’s recent book might be worth your while. Beard is an English historian generally acknowledged as an authority on the subject, and Emperor of Rome is her latest offering. As she tells the story, being emperor was challenging – and sometimes dangerous – work.

Julius Caesar, the dictator assassinated at the age of 55, was the key transitional figure between the Roman Republic and the subsequent world of emperors. But before lamenting the demise of representative government and its replacement by autocracy, it’s worth noting how the old Republic actually functioned.

Beard describes it as “a sort-of democracy,” or a power-sharing system dominated by the rich, who were the only ones allowed to hold office. Most political positions were term-limited and held jointly. Her summary is succinct: “The underlying principle of the Republic was: you never held power for long, and never alone.”

|

| Related Stories |

| Caesar and Alexander – heroes, villains, or both?

|

| Who was Pontius Pilate, the man who sentenced Jesus to death?

|

| England’s warrior queen

|

Beard is also unsentimental about Caesar’s assassins, characterizing their action as “a model for political murder lasting into the modern world.” In her estimation, they were “a predictably mixed group of high-principled freedom fighters, malcontents and self-interested power seekers.” And the result was a prolonged civil war that “brought about the very thing they claimed to be fighting against: permanent one-man rule.”

One of the most interesting emperors was Hadrian.

Born near Seville in modern Spain, Hadrian became emperor in 117 and ruled for 21 years until his death in 138. He was a poet, a great admirer of Greek culture, and given to openly travelling with his young male lover. But he could also be totally ruthless if Roman interests, or his own, were threatened. The brutal suppression of the Jewish Revolt (132-136) bears witness to what he could do.

And he spent a lot of time away from Italy.

For instance, he was travelling between 121 and 125, touching base in Britain, Germany, France, Spain, Syria, Turkey and Greece. And he was on the move again between 128 and 134, all the while putting his personal imperial brand on far-flung parts of the empire. Sometimes, there was a direct military purpose to his itinerary; other times, not.

The idea of emperor was associated with military valour and glory. An emperor was supposed to be a successful general, which in turn required opportunities to strut your stuff. But, in fact, most of the empire dated from the days of the Roman Republic, and opportunities for glory via fresh conquests were correspondingly limited.

A major psychological turning point came late in the reign of Augustus, the first emperor. At the Battle of Teutoburg Forest in Germany, the Romans were catastrophically defeated by an alliance of Germanic tribes, losing up to 20,000 soldiers in the process. It was a wipe-out of an entire army, after which imperial focus tilted towards defence.

Beard puts the ensuing dilemma this way: “There was a clash, in other words, between the image of the emperor as commander-in-chief of legions that were effectively a police force on guard duty, and the image of the emperor as heroic general, in the traditional Roman mould that went back to the Republic, leading his troops into battle in a project of ever greater expansion.”

However, there were occasions when the lure of conquest proved irresistible. Britain was the most spectacular example.

While the island posed no security threat and had successfully resisted Caesar, it retained a grip on the Roman imagination as a “final frontier at the edge of the world.” And when Claudius, the fourth emperor, yielded to temptation in the middle of the first century, it took four legions to do the job without ever gaining control of the entire island. Still, they did hold on to parts of it until the early fifth century.

Obviously, the relationship between emperor and army was crucial. Bonding was essential.

The army was thus well looked after financially, not only in pay but also in retirement and sickness benefits. And it went further. The emperor needed to be seen as “one of the lads.”

So when he was with the troops, Hadrian took care to share the same kind of accommodation and eat the same camp food. This seeming equality wasn’t a reflection of reality, but it served a political purpose.

One is reminded of the mid-20th century British prime minister Harold Wilson and his public affection for pipe and pint. Privately, Wilson preferred cigars and brandy.

Troy Media columnist Pat Murphy casts a history buff’s eye at the goings-on in our world. Never cynical – well, perhaps a little bit.

For interview requests, click here.

The opinions expressed by our columnists and contributors are theirs alone and do not inherently or expressly reflect the views of our publication.

© Troy Media

Troy Media is an editorial content provider to media outlets and its own hosted community news outlets across Canada.