Maj. Gen. Leslie Groves had a reputation for getting things done

The theoretical physicist J. Robert Oppenheimer is conventionally described as the father of the atomic bomb. He was, after all, the chief scientist on the three-year Manhattan Project that culminated in the August 1945 atomic bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, and the consequent ending of the Second World War.

The theoretical physicist J. Robert Oppenheimer is conventionally described as the father of the atomic bomb. He was, after all, the chief scientist on the three-year Manhattan Project that culminated in the August 1945 atomic bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, and the consequent ending of the Second World War.

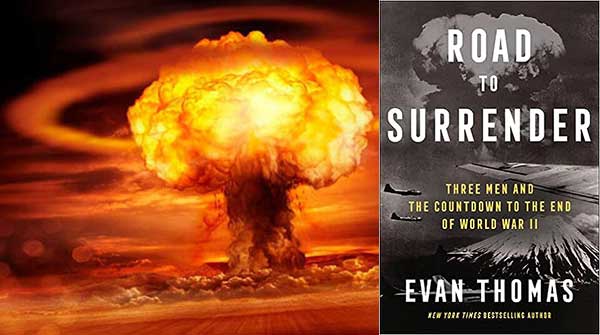

But as the new book by Evan Thomas – Road to Surrender – makes clear, Oppenheimer had an enabler. Indeed, you could plausibly describe Maj. Gen. Leslie Groves as the Manhattan Project’s indispensable man.

Born in 1896, Groves was a career army officer with a reputation for getting things done. He wasn’t what you’d characterize as a nice man. Descriptors like abrasive, sarcastic and demanding have been freely deployed. Eventually, it was this disinterest in human relationship norms that put a ceiling on his military career.

|

| Related Stories |

| The building of the Atomic Bomb Part 1

|

| The building of the Atomic Bomb Part 2

|

| The building of the Atomic Bomb Part 3

|

| The building of the Atomic Bomb Part 4

|

The Manhattan Project was a huge, sprawling endeavour involving many disciplines and crossing multiple jurisdictions. It needed strong, single-minded direction. And as one suffering subordinate later put it, “if I had to do my part of the atomic bomb project over again and had the privilege of picking my boss, I would pick General Groves.”

Groves was also the man who selected Oppenheimer for the premier scientist role. It wasn’t a slam-dunk choice or one devoid of risk. Oppenheimer had familial communist connections and there were expressed security concerns. But Groves cast them aside.

Although U.S. President Harry Truman embraced responsibility for using the atomic bomb, Groves thought otherwise. Rather than being in control, Truman was “like a little boy on a toboggan,” swept along by events already in motion and beyond his full understanding.

There’s truth in that.

Truman was Franklin D. Roosevelt’s third vice-president, and Roosevelt gave him little or nothing to do. Truman was, to put it mildly, out of the loop, knowing nothing about the atomic bomb until he became president when Roosevelt died on April 12, 1945.

And while Truman was aware of the plans for a second strike if Japan didn’t surrender post-Hiroshima, he didn’t know the specific timing of Nagasaki until after the bomb had been dropped. Only then did he assert personal control, forbidding any further atomic strikes without his express approval.

Groves, for his part, had neither ambivalence nor queasiness about using the bomb. His only interest was effectiveness, the criterion for which would be inducing Japan’s surrender, thus ending the war and preventing the enormous American casualties inherent in an invasion.

So he took issue with Secretary of War Henry Stimson’s insistence that Kyoto be ruled off-limits. To Groves, Kyoto’s revered status as Japan’s ancient capital and sacred cultural centre was all the more reason to target it. Maximizing effectiveness meant hitting where it would hurt the most.

An interesting aspect of the Thomas book is the way it lifts the covers off what was happening in Japan, where the war was essentially run by a consensus-bound Big Six, comprised of the prime minister, the foreign minister and four senior military figures. In essence, the military called the shots.

And whatever others thought, the military didn’t believe it was beaten. Instead, the prevailing orthodoxy was the concept of the impending Decisive Battle.

Involving thousands of kamikaze planes and hundreds of suicide bombers in small speedboats, the intention was “to sink up to half of the American invasion fleet” before it landed. And the Americans who made it to shore would be met by around 900,000 regular Japanese soldiers, supplemented by a huge civilian force armed with spears, pitchforks and the like. Thomas quotes from a Japanese handbook for civilians: “When engaging tall Yankees, do not swing swords or spears sideways or straight down; thrust must be straight into their guts.”

Thomas summarizes the strategy this way: “The Japanese do not have to ‘win’ the Decisive Battle. They just have to make the cost of victory unbearable to the Americans.”

As the Japanese military still resisted surrender after Nagasaki, U.S. Army Chief of Staff George Marshall began casting around for alternatives. One of these involved using up to nine atomic bombs as battlefield weapons in support of the planned beach landings. Meanwhile, Truman mulled approving Tokyo as a third target. Fortunately, Emperor Hirohito intervened, and Japan surrendered.

After the July 16 atomic bomb test in the New Mexico desert, Groves’ deputy, General Farrell, opined that the war was over. “Yes,” replied Groves, “after we drop two bombs on Japan.”

As amoral or coldblooded as that may sound, perhaps Groves was just a realist.

Troy Media columnist Pat Murphy casts a history buff’s eye at the goings-on in our world. Never cynical – well, perhaps a little bit.

For interview requests, click here.

The opinions expressed by our columnists and contributors are theirs alone and do not inherently or expressly reflect the views of our publication.

© Troy Media

Troy Media is an editorial content provider to media outlets and its own hosted community news outlets across Canada.