Canada faces new pressures on any attempts to ramp up international trade.

Canada faces new pressures on any attempts to ramp up international trade.

In 1994, the United States, Mexico and Canada created a free-trade region with the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA).

Considering that the U.S. has been the largest economy in the world from 1994 to now, NAFTA was a true asset for the Canadian economy. It’s estimated that the “total merchandise trade between Canada and the United States has more than doubled since 1993, and has grown over nine-fold between Canada and Mexico.”

However, former U.S. president Donald Trump deemed this trade deal detrimental for American jobs and wanted a renegotiation. He argued that the new treaty would “create nearly 100,000 new high-paying American auto jobs, and massively boost exports for our farmers, ranchers and factory workers. It would also bring trade with Mexico and Canada to greater heights, with higher levels of fairness and reciprocity.”

Ottawa and Mexico have accepted this renegotiation, resulting in the Canada-United States-Mexico Agreement (CUSMA), which replaced NAFTA on July 1, 2020.

Large portions of CUSMA are similar to the dispositions of NAFTA. For example, the tariff-free access to the North American marketplace for Canada’s export-dependent beef, pork and grain sectors, with improvements to certain elements.

The new deal also raises Canada’s duty-free level from C$20 to C$150 and the sales tax increase from C$20 to C$40. However, that only applies for U.S. goods ordered online. This solution will be profitable for Canadian customers but not for Canadian retailers, especially considering the strength of American digital giants.

In addition, there’s better protection for technology firms whose copyrights now extend to 70 years, up from 50 under NAFTA. And governments can no longer request source code from tech companies, and duties on electronic transmissions are prohibited.

In addition, there’s better protection for technology firms whose copyrights now extend to 70 years, up from 50 under NAFTA. And governments can no longer request source code from tech companies, and duties on electronic transmissions are prohibited.

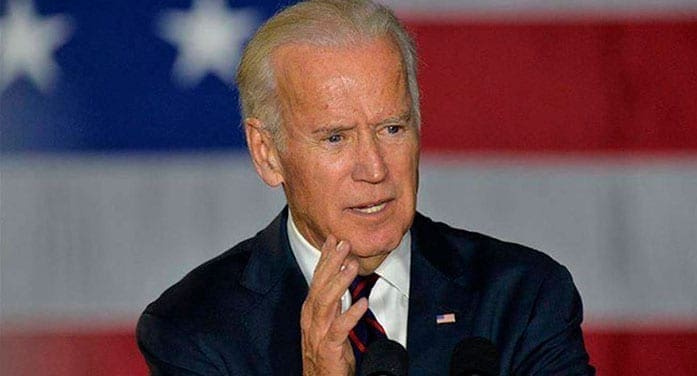

However, some aspects of this new treaty show that it might be more beneficial for the United States than Canada and Mexico. Developed during the trade war waged by the Trump administration, CUSMA won’t prevent protectionist measures such as the 10 percent tariffs on aluminum and the 25 percent tariffs on steel imposed by the Trump administration at the end of May under Section 232 of the Trade Expansion Act. Moreover, considering that U.S. President Joe Biden is in favour of some protectionism, uncertainty remains, threatening Canadian trade.

North American protectionism is reinforced through numerous clauses under CUSMA. For example, to qualify for zero tariffs, the vehicle industry must produce 75 percent of a vehicle’s components in North America, up from the 62.5 percent under NAFTA. And 70 percent of the steel and aluminum used in auto production must be produced and purchased in North America.

According to Clifford Sosnow, co-chair of Fasken’s International Trade and Investment Group, the energy space in North America will be less integrated than under NAFTA: “Under NAFTA, governments were prohibited from discriminating against other NAFTA party coal, uranium or petrochemical products with import or export taxes other than duties.” However, CUSMA removes this aspect.

CUSMA can also hinder potential trade treaties for Canada with specific countries. Section 31.10 of the agreement says that before negotiating a free trade agreement with a “non-market country,” the nation must inform the other CUSMA countries, at least three months before starting negotiations. In the United States, 11 countries meet this definition, including China. This could be problematic for potential trade agreements with Beijing, particularly for Canada. The U.S. could act as the judge of these agreements and place political pressure on the negotiations.

CUSMA is necessary for the Canadian economy. Refusal of this trade deal may prove to be worse than signing it. With most of the NAFTA disposition preserved, it remains a good tool for trade.

However, Canada must be aware that protectionism has returned and will make international trade more complicated and more regulated than before.

Moreover, the COVID-19 pandemic has increased protectionist behaviour in North America, along with the rest of the world. Canada might have a hard job defending its interests.

Alexandre Massaux is a research associate with the Frontier Centre for Public Policy.

Alexandre is a Troy Media contributor. For interview requests, click here.

The views, opinions and positions expressed by columnists and contributors are the authors’ alone. They do not inherently or expressly reflect the views, opinions and/or positions of our publication.

© Troy Media

Troy Media is an editorial content provider to media outlets and its own hosted community news outlets across Canada.