The following is an excerpt from The Victim Cult: How The Grievance Culture Hurts Everyone And Wrecks Civilizations by Mark Milke. In this excerpt, Milke details how the “new” definition of racism from Ibram X. Kendi and others hollow out hard facts and reasoned analyses when a monocausal explanation – racism – is offered up for all observed disparities between cohorts.

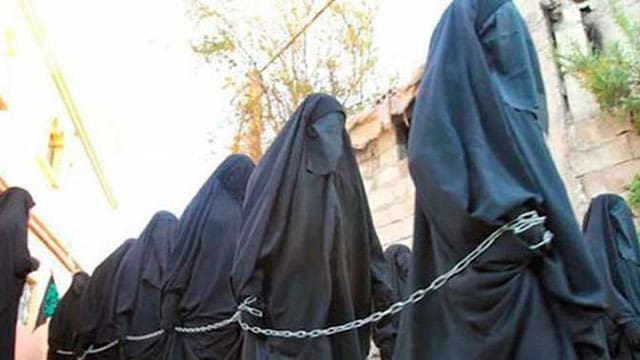

The moral stain common to the rest of humanity – slavery – was also present in the lush rainforests of the upper and isolated inlets and interior of the Pacific Northwest. “Slavery was a permanent status in all Northwest Coast societies,” wrote anthropologist Leland Donald in his 1997 book, Aboriginal Slavery on the Northwest Coast of North America. Slaves could end up in that predicament for any number of reasons: captured as part of inter-tribal warfare, after inter-tribal raids, born to an existing slave, or if they were an orphan (which could lead to enslavement even in one’s own tribe).

The moral stain common to the rest of humanity – slavery – was also present in the lush rainforests of the upper and isolated inlets and interior of the Pacific Northwest. “Slavery was a permanent status in all Northwest Coast societies,” wrote anthropologist Leland Donald in his 1997 book, Aboriginal Slavery on the Northwest Coast of North America. Slaves could end up in that predicament for any number of reasons: captured as part of inter-tribal warfare, after inter-tribal raids, born to an existing slave, or if they were an orphan (which could lead to enslavement even in one’s own tribe).

A wife could be sold and enslaved through a deliberate attempt by her husband at humiliation (recorded among the Haida, for example). One could even end up in voluntary slavery to pay off one’s debts. As with slavery elsewhere in the world, captives in the Pacific Northwest were considered property. They were sometimes given as gifts, including at potlatches; on other occasions, slaves substituted as payment for fees due to shamans.

Slavery in the Pacific Northwest developed sometime between 500 B.C. and A.D. 500, long before European contact.

Early indigenous peoples also possessed other practices that predated contact with the British and Europeans: cannibalism and the killing of slaves; the latter occurred for a variety of reasons: funeral feasts, the building of a new home, a new title, the erection of a totem pole, or as part of the ceremony at potlatches.

A Russian Orthodox priest recounted how, in one Sitka ceremony, four slaves were strangled as part of the ritual upon the appointment of a new clan chief. In one account of a ceremony at Fort Rupert, British Columbia, two female slaves were burnt as part of a ceremonial display, although they volunteered believing they would be resurrected four days hence. The regional slave trade was numerically smaller in absolute terms, though similar as a proportion of some local populations, ranging from almost nil to as high as 40 percent; the average was 15 percent of the local population.

Anti-slavery advocacy and animosity around the world were driven by evangelical Christian anti-slavery societies, whose religious objections to slavery were grounded in their view of men as made in God’s image regardless of race equal in his eyes. Such abolitionists also found a political champion in William Wilberforce, the British parliamentarian whose decades-long efforts to abolish slavery were inspired by his own evangelical faith. Wilberforce’s first known act of opposition to the slave trade occurred in 1773, when he was 14 years old, in a letter to a York newspaper where he wrote: “in condemnation of the odious traffic in human flesh.”

Anti-slavery advocacy and animosity around the world were driven by evangelical Christian anti-slavery societies, whose religious objections to slavery were grounded in their view of men as made in God’s image regardless of race equal in his eyes. Such abolitionists also found a political champion in William Wilberforce, the British parliamentarian whose decades-long efforts to abolish slavery were inspired by his own evangelical faith. Wilberforce’s first known act of opposition to the slave trade occurred in 1773, when he was 14 years old, in a letter to a York newspaper where he wrote: “in condemnation of the odious traffic in human flesh.”

Seven years later, Wilberforce was elected as a member of parliament. Wilberforce’s early convictions showed publicly in his first major assault on slavery in 1789 with his May 12 speech in parliament on the matter. In it, Wilberforce condemns not the slaveholders first but instead takes responsibility himself and also for his nation: “I mean not to accuse any one, but to take the shame upon myself in common with the whole Parliament of Great Britain for having suffered this horrid trade to be carried on under our authority,” said Wilberforce.

It was a long, eloquent, and even charitable speech meant to persuade slaveholders and their parliamentary supporters with reason and an appeal to conscience. Wilberforce then moved 12 resolutions, including an early plea for abolition, though that and the others failed. He followed up with 10 anti-slavery bills between 1791 and 1807. Due to his efforts and others, in one month alone in 1807, parliament received 800 separate petitions with 700,000 signatures calling for an end to slavery. At the time, the population of Great Britain was just 10.9 million.

Wilberforce would expend his entire parliamentary career and ultimately his life to effect abolition. One of Wilberforce’s first abolition bills, in 1793, fell short by just eight votes, but successes included the Foreign Slave Trade Bill (in 1806) and the Abolition of the Slave Trade Act (in the House of Lords, in 1807). While the trade was outlawed in 1807, slavery in the empire was still allowed until 1833 when the government finally introduced the Slavery Abolition Act, which abolished slavery and freed slaves across the British Empire effectively the following year. That was eight years after Wilberforce left parliament due to ill health. Gravely ill in 1833, when the Whig government introduced the compromises necessary to obtain passage of the Slavery Abolition Act, Wilberforce would die just two days later on July 29, 1833, at the age of 73.

Decades later, Great Britain’s edict was finally matched in the United States by President Abraham Lincoln’s 1863 Emancipation Proclamation. Even then, slavery was slower to disappear from the Pacific Northwest than from the rest of the United States, in part because the trade in an isolated corner of North America barely registered in public consciousness.

In western Washington State, a treaty between the Makah and the United States government obliged the Makah to end slavery. In 1869, the section of the treaty on slavery was not yet enforced, although it apparently led to better treatment of slaves. The chronicler, James Swan, was optimistic slavery would soon end: “It is to be hoped that, in a few years, under the judicious plan of the treaty, slavery will be gradually abolished, or exist only in a still milder form.” In 1878, Hall Young, a missionary, freed some slaves from the Stikine but noted that their owners objected and, in some cases, only pretended to liberate slaves. Writing in 1888, United States Admiral Alfred P. Niblack wrote of how the Russians had, when they controlled Alaska, made some effort to alleviate “the hardships of this wretched [slave] class in the vicinity of the Sitka.”

Slavery in Alaska was still ongoing at the time of the 1867 purchase by the Americans, with reports of slavery in Alaska continuing until the 1890s. The remote nature of the Pacific Northwest helps explain the slow death of slavery in the region: however, the combination of the British and American presence, pressure, and agreements led slavery to finally disappear from the region by 1900.

In the context of today’s grievance narratives, the worldwide history of slavery is useful to recount to make this point: Almost everyone’s ancestral tree has the awful mark of slavery on it. And it was only the colonial-era British who were determined to wipe slavery from humanity’s list of acceptable practices.

Slavery, in fact, touched nearly every corner of our world until very recently.

Two centuries ago, few desired its elimination, and even fewer were willing to fight that assumption. The modern bias against the colonial British is often one-sided, tallying up colonial ills but not benefits. That makes history incomplete: Britain was the first to even attempt to remove a longstanding scourge of mankind from mankind, over the objections of rulers and populations in much of the rest of the world, who only came to recognize such civil rights later.

That is why romanticizing our own tribes is often faulty and folly: We too easily ignore – in an age where victim narratives are driven by a focus on the sins of Western nations but rarely those of other civilizations – the benefits another tribe introduced into ours.

Just as rarely do the critics consider what the world might look like had the West and its ideas and actions, including its positive contributions such as the abolitionist movement, been absent. Everyone’s ancestors, at some point, made everyone else’s life, as Thomas Hobbes wrote, solitary, poor, nasty, brutish, and short. It helps to recall that truth, lest modern victim-cults continue to be enamoured with long-dead tribes.

The earliest abolitionists, evangelical and Christian, British and imperial, helped rescue all of humanity’s tribes – be they European, those in the Americas, in Africa and the Arab world – from humanity’s most enduring sin and from their own contemporaries who practised it. It was a significant accomplishment.

Next: How early Asian Americans trumped prejudice

Mark Milke, Ph.D., is a public policy analyst, keynote speaker, author, and columnist with six books and dozens of studies published across Canada and internationally in the last two decades. Visit www.victimcult.com for more information.

Mark is a Troy Media contributor. For interview requests, click here.

The opinions expressed by our columnists and contributors are theirs alone and do not inherently or expressly reflect the views of our publication.

© Troy Media

Troy Media is an editorial content provider to media outlets and its own hosted community news outlets across Canada.