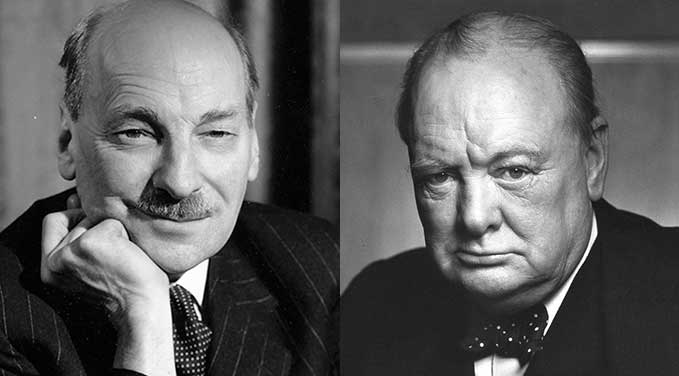

For the longest time, Clement Attlee lived in Winston Churchill’s shadow. Where Churchill was flamboyant, charismatic and eloquent, Attlee was reticent, dull and rhetorically challenged. Churchill was larger than life and Attlee was the little man who seemed to blend into the woodwork.

For the longest time, Clement Attlee lived in Winston Churchill’s shadow. Where Churchill was flamboyant, charismatic and eloquent, Attlee was reticent, dull and rhetorically challenged. Churchill was larger than life and Attlee was the little man who seemed to blend into the woodwork.

After becoming leader of the United Kingdom’s Labour Party in 1935, Attlee led them into a wartime coalition government in which he served as deputy prime minister to Churchill between 1940 and 1945. Then, to everyone’s astonishment, he decisively defeated Churchill in the U.K’s first general election following the European conclusion of the Second World War.

Attlee was born in 1883, which made him nine years younger than Churchill. Growing up in late Victorian England with the British Empire at its apogee, they had significant things in common.

They were both intensely patriotic and devoted to the Crown. And they were both imperialists, although Attlee subsequently developed a much more nuanced view, such that he became an active proponent of Commonwealth rather than Empire.

Politically, they even briefly shared party alignment. Attlee started as a Conservative and once hailed Churchill “as a rising hope of our party.” But by his mid-20s, Attlee’s perspective had changed. He was now a socialist.

Churchill has always been a controversial figure, revered by some and despised by others. He was, to put it mildly, complicated.

Attlee took a sophisticated view of this complexity, comparing Churchill to a layer cake: “There was a layer of 17th century, a layer of 18th century, a layer of 19th century, and possibly even a layer of 20th century. You were never sure which layer would be uppermost.”

The political relations between the two men were sometimes testy and Churchill could say uncomplimentary things. But while Attlee invariably stood his ground, he had genuine admiration and affection for Churchill. And rhetorical shots notwithstanding, this never changed.

As early as 1924, Attlee publicly defended Churchill on the hugely controversial issue of the disastrous 1915 Gallipoli campaign, which Churchill sponsored in his capacity as First Lord of the Admiralty during the First World War. Having been there as a soldier, Attlee had personal skin in the game and might have been expected to resent the plan’s author.

He didn’t.

Instead, he thought the concept was strategically sound and carried the potential to shorten the war. The failure, in his view, was down to “elderly and hidebound” generals who weren’t up to the job of executing such an innovative strategy.

But by far the biggest contributor to Attlee’s admiration was his observation of Churchill’s Second World War leadership, which he experienced close up through his participation in the all-important five-member War Cabinet. In his estimation, Churchill was indispensable to victory.

It wasn’t only a matter of Churchill’s ability to rally the public with inspirationally defiant speeches. There was also his decisiveness, resoluteness and willingness to stand up to the generals. Like many men who’d fought in the First World War, Attlee had no illusions about the infallibility of military leaders and valued the fact that Churchill felt the same.

Much later, when both had retired from active politics, Attlee continued to enjoy opportunities for Churchill’s company, even if the latter’s deafness meant that the conversation went one way. As he put it: “What a career! What a man! We shall not see his like again.”

While Churchill’s reputation has taken some hits in recent years, Attlee’s has risen. For better or worse, the Labour government he led between 1945 and 1951 is seen as Britain’s most radical in the 20th century. And the Britain of today bears much more of Attlee’s stamp than Churchill’s.

Winston Churchill: ruffian or hero? by Pat Murphy

Even with his many flaws, Churchill was a very useful guy to have around when the chips were down

Churchill once declared that history would be good to him because he intended to write it himself. Attlee was different.

Whatever his private thoughts, ostentatious self-regard just wasn’t Attlee’s style. He often approvingly quoted a comment made to him by Conservative MP Thomas Moore: “You know when I was young I was always talking about my conscience. But I thought it over and I came to the conclusion that what I called my conscience was just my own bloody conceit.”

There’s a poignant vignette from the day of Churchill’s January 1965 funeral. Attlee, then 82-years-old and ailing, stumbled at the entrance to St. Paul’s Cathedral and was photographed sitting on the bottom step, bent over his cane, while collecting himself. Old school to the end.

Pat Murphy casts a history buff’s eye at the goings-on in our world. Never cynical – well, perhaps a little bit. For interview requests, click here.

The opinions expressed by our columnists and contributors are theirs alone and do not inherently or expressly reflect the views of our publication.

© Troy Media

Troy Media is an editorial content provider to media outlets and its own hosted community news outlets across Canada.