Cognac is a type of brandy produced in the Charente region of France, centred around the towns of Cognac and Jarnac, and stretching from the Île de Ré to the Gironde Estuary on the Atlantic coast, to Angoulême and the foothills of the Mastiff Central.

Cognac is a type of brandy produced in the Charente region of France, centred around the towns of Cognac and Jarnac, and stretching from the Île de Ré to the Gironde Estuary on the Atlantic coast, to Angoulême and the foothills of the Mastiff Central.

The Cognac Delimited Region, the exclusive area where cognac can be produced, lies across the French departments of Charente and Charente Maritime and includes several districts of the Dordogne and Deux-Sevres departments in western France.

Brandy refers to any distillate that’s derived from a fermented fruit juice or fruit pulp. If the brandy is made from grapes, it’s usually just referred to by the generic description brandy. If it’s made from another fruit, then its origins are added to the term brandy.

Thus Calvados, an apple-cider-based distillate produced in Normandy, is usually termed an apple brandy. Kirsch, a distillate based on the fermentation of the juice, pulp and stones of the Morello cherry, is likewise referred to as cherry brandy.

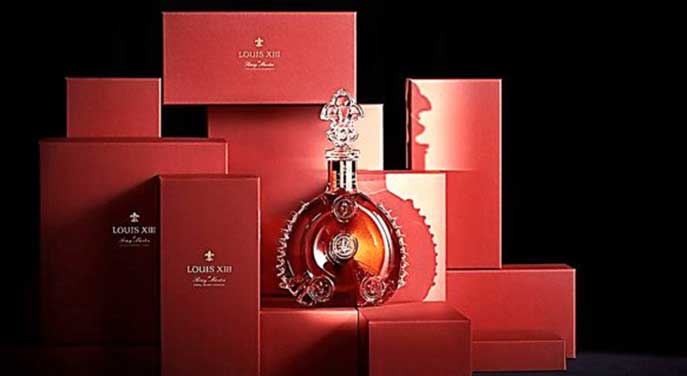

Photo by Kevin Sicher

Usually, spirits intended to produce brandy are distilled at alcoholic strengths of less than 80 percent alcohol by volume (ABV). Spirits with higher alcoholic strength tend to lose the flavour and aromatic compounds, or congeners, which give the final distillate its distinctive taste.

There are some exceptions. Spanish brandy, for example, may consist of a blend of a high ABV spirit mixed with a more aromatic spirit with a lower ABV.

Distillates produced at very high ABVs are typically not called brandies, although usage of the term depends on local regulation, even if they are fruit-based. For example, Cîroc, a grape-based distillate from roughly the same geographic region where cognac is produced, is distilled to an ABV of around 95 percent and is sold as a vodka rather than as a brandy.

The origins of cognac

The term brandy is a corruption of the Dutch term brandywein or burnt wine. The term burnt refers to the fact that the wine had been distilled.

Local lore has it that cognac was invented when Dutch merchants, in order to reduce their shipping costs, first distilled the local wine to reduce its bulk. Their intent was to convert it back to wine by adding water when it arrived at its destination. On doing so, however, they discovered that rather than getting wine, they got an entirely different product: brandy.

It’s a colourful story but highly unlikely.

It’s not clear when distillation first arrived in the Charente region. The first reference to eau de vie du Coniack dates from 1517. It’s likely that distillation arrived at some point between the mid-14th century and the 15th century.

The first stills were likely very small, operated by individual winemakers and, like the Gascon brethren in Armagnac, relied on a single distillation. Distilling wine that could not be shipped or sold domestically was a way of preserving the caloric and economic value of the wine.

In addition, alcohol was in high demand, both for its medicinal uses and to fortify wines before long sea villages. Distilling wine into alcohol was profitable and a way for wine makers to supplement their income.

During the 16th century, alcohol was being used to produce a wide range of elixirs and potions. It was also used to extract aromatic and beneficial compounds from many kinds of plants.

During the 16th century, alcohol was being used to produce a wide range of elixirs and potions. It was also used to extract aromatic and beneficial compounds from many kinds of plants.

In the hot, humid holds of ships, new wine would quickly turn to vinegar. The bacterium that converts alcohol into vinegar, acetobacter aceti, cannot tolerate alcohol levels higher than 20 percent. That’s the reason that wine intended for long shipments would be fortified. That practice eventually gave rise to wines like port, sherry and Madeira.

By the mid-17th century, distillation was widespread throughout the Charente region. Many winemakers still operated small backyard stills, but by now large distillers had emerged.

Their stills, using copper for construction, were much larger than the original farmyard stills. Moreover, unlike early distillers, these new producers, many of whom were Dutch merchants, were not distilling their own wine. Instead, they bought wine from local producers to distill.

There were still two additional developments that had to occur before the modern Cognac industry could emerge: double distillation and a more consistent product.

Local lore has a variety of explanations for the origins of double distillation.

One is that double distillation was developed by the Dutch to reduce the bulk of the brandy being shipped. In addition, the wine tax being levied on brandy was based on volume. So a more concentrated brandy would pay less tax.

This may be true, but it probably isn’t. Significantly reducing the bulk of the local brandy through a second distillation would have completely changed its taste. Diluting it by adding more water would not have restored it to what would have been produced from a single distillation.

A second explanation, by French historian Claude Masse, is that double distillation was first invented by an unknown chemist in La Rochelle sometime in the late 17th century.

To speak of the invention of double distillation is a misnomer, however. Double distillation was simply repeating what was by then the well-known process of distillation. Presumably, when distillers had a batch of distillate that tasted or smelled bad, they would simply redistill it to remove the impurities.

Double distillation was likely occurring across the Charente long before any one person officially discovered it.

In Gascony, Armagnac producers lacked access to a seaport for shipping. Their market remained small and local. Their stills remained equally small. In the Charente, however, rising international demand for the local brandy drove ever higher production levels. One way of responding to the higher demand was to build larger stills.

Early stills had been built out of ceramic and later iron, but neither material worked very well for building large stills.

Copper, which is very malleable, was ideal. Until the 17th century, however, copper was relatively scarce and expensive. Readily available copper from new discoveries in Eastern Europe and elsewhere made it much more plentiful and economical and paved the way for its use in building large stills.

Large stills have the advantage of being much more economical. The use of larger stills, however, changed the taste and aroma of the distillate produced. They didn’t yield as refined a spirit as a small still.

As the stills in the Charente got bigger, distillers realized that the eau de vie of a single distillation from large stills would not yield as fine a spirit as that from a smaller still. If they wanted to replicate the quality of the original smaller stills, they would have to do a two-step distillation. That was likely the origin of double distillation.

Irish whiskey distillers in the second half of the 19th century discovered the same principle. In response to skyrocketing demand for Irish whiskey, distillers built ever larger stills. By the late 19th century, the largest stills in the world were all in Ireland. Giant stills, however, could not produce the same quality of whiskey, even after two distillations, so Irish distillers switched to a triple distillation process to create the style of whiskey consumers wanted.

During this period, the quality of cognac production tended to be very inconsistent. Distillers relied on their sense of taste and smell when determining cut points, i.e. the points at which the distiller would begin and end the collection of spirit intended for consumption. The alcohol content of the resulting brandy, and by extension its taste and aroma, would vary widely.

The brandy produced was typically distilled to about 48 percent ABV, creating a drink that would have been much more aromatic and pungent than today’s cognac and more akin to modern Armagnac. Brandy destined for England would be distilled to a higher proof, producing a more refined, lighter product, a characteristic that defines the British cognac market to this day.

The invention of the alcoholmeter, a hydrometer that measures the alcoholic strength of liquids, by Johann Tralles in the late 18th century, and its further refinement by Joseph Gay-Lussac, allowed distillers to accurately measure the cut points at which they would begin and end the collection of distillate destined to become brandy. Consistent cut points, in turn, created a more consistent product across the region.

By the 18th century, the practice of double distillation, and the unique set up of the iconic shaped pot still, wine preheater and worm tube condenser, had become enshrined as Charentaise distillation.

Although there was no requirement to use this specific distillation set up and although the distillation process itself was unregulated, Charentaise distillation, enforced by the requirements of the cognac houses that were then emerging, was increasingly the norm in the region.

Next: Understanding cognac: The rise of the cognac houses

Joseph V. Micallef is an historian, best-selling author, keynote speaker and commentator on wine and spirits. Joe holds the Diploma in Wine and Spirits and the Professional Certificate in Spirits from the Wine and Spirits Education Trust (London).

The views, opinions and positions expressed by columnists and contributors are the authors’ alone. They do not inherently or expressly reflect the views, opinions and/or positions of our publication.

© Troy Media

Troy Media is an editorial content provider to media outlets and its own hosted community news outlets across Canada.