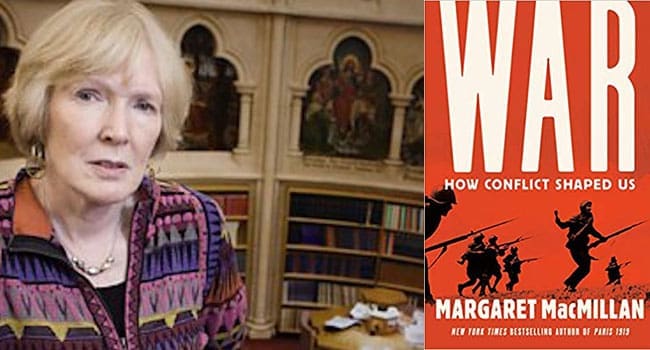

On Remembrance Day, as chance would have it, I was reading Margaret MacMillan’s latest book, War: How Conflict Shaped Us. MacMillan is a Canadian historian most famous for two works connected to the First World War – Paris 1919 and The War That Ended Peace.

On Remembrance Day, as chance would have it, I was reading Margaret MacMillan’s latest book, War: How Conflict Shaped Us. MacMillan is a Canadian historian most famous for two works connected to the First World War – Paris 1919 and The War That Ended Peace.

Her new book builds on a series of lectures she delivered for BBC Radio Four in 2018. Organized into nine thematic chapters, it’s a fluid read. MacMillan writes well.

Here are some things that caught my eye.

Culture

MacMillan defines culture broadly as the values, beliefs, ideas and institutions that animate us. And she notes that culture has shaped warrior societies since the dawn of history. These societies honour bravery, endurance, toughness and the willingness to face death.

From ancient Sparta to Rome to Prussia, cultures have elevated personal characteristics associated with battlefield success. Sometimes this was particularly emphasized within social sub-groups. For instance, the Anglo-Irish upper classes provided a disproportionate number of officers to the British army.

Nor is the warrior society phenomenon peculiarly European. Think of Genghis Khan’s Mongols. Or Indigenous North American peoples like the Sioux or the Comanche. Or Nepal’s Gurkhas.

It’s also simplistic to think of war as a male activity driven by patriarchal social structures. While it’s true that military hierarchies are traditionally male and the fighting in most wars has been done largely by men, women have always played a key role in the reinforcing culture.

There were the Spartan mothers who told their sons “to come home with their shields or carried, dead, on them.” And the First World War women who made a thing of bestowing white feathers on civilian men of military age, not to mention the militant suffragettes who supported conscription.

Cultures, mind you, can change over time.

As recently as the 17th century, Swedish soldiers “were the terror of Europe.” But “now we associate Sweden with the Nobel Peace Prize or international mediation.”

And something similar can be said of the Swiss, whose fearsome mercenaries were once highly prized by anyone who could afford to hire them.

Technology

MacMillan recognizes technology as a military facilitator, noting that “some societies encourage invention and innovation while others adopt new weapons or techniques slowly or not at all.”

Much of Europe’s early modern dominance can be ascribed to this distinction. Whereas 16th-century India, China and the Ottoman Empire matched Europe in wealth and knowledge, the latter’s new found propensity for applying that knowledge gave it a technological edge. And that edge propelled the dominance that has only ebbed in recent decades.

Historically, military innovations have generated defensive responses. MacMillan sees it as a perpetual race.

The ancient introduction of metal-tipped spears and arrows led to the development of armour. The deadly deployment of mounted warriors was eventually countered by innovations in infantry tactics whereby disciplined, deep and densely-packed rows formed “lethal obstacles against which horses and riders dashed themselves in vain.” And so on.

Small innovations also mattered.

The invention of the stirrup made mounted warriors far more formidable by virtue of putting less strain on their legs. And the fact that Mongol warriors wore silk undershirts rendered them less susceptible to infections from arrow wounds because the silk tended to wrap around the arrow heads.

Soldiers

The Prussian field marshal who observed that “No plan survives contact with the enemy” succinctly underlined the inherent chaos of war. You may think you’ve sussed all the angles, but reality quickly tells you otherwise. The term ‘fog of war’ isn’t just a clever turn of phrase.

For many soldiers, this can be disorienting, even terrifying. But not for all.

Some find it exciting and relish testing themselves. There’s also the attendant buzz of an environment where the usual social norms regarding life, death and destruction have either vanished or become significantly attenuated.

This can make people uneasy. It’s not considered respectable. When BBC executive Lord Reith was looking for a publisher for his memoirs, the fact that his war experiences didn’t tow the prevailing line caused difficulties.

And MacMillan tells of interviewing a Canadian general who spoke candidly only after the tape recorder was turned off: “It was, he said, like riding a very fast motorcycle. The knowledge that you could crash and die at any moment added to the thrill.”

War is complicated and thinking about it can be uncomfortable.

Pat Murphy casts a history buff’s eye at the goings-on in our world. Never cynical – well perhaps a little bit.

For interview requests, click here. You must be a Troy Media Marketplace media subscriber to access our Sourcebook.

The views, opinions and positions expressed by columnists and contributors are the author’s alone. They do not inherently or expressly reflect the views, opinions and/or positions of our publication.