He’s a forgotten figure now but there was a time when anyone following the news cycle would have known who Caryl Chessman was. Sentenced to death in California on June 25, 1948, Chessman won eight stays of execution until the gas chamber finally caught up with him on May, 2, 1960. In the process, he became an international poster boy for the anti-capital punishment movement.

He’s a forgotten figure now but there was a time when anyone following the news cycle would have known who Caryl Chessman was. Sentenced to death in California on June 25, 1948, Chessman won eight stays of execution until the gas chamber finally caught up with him on May, 2, 1960. In the process, he became an international poster boy for the anti-capital punishment movement.

Chessman was what you’d call a tough nut. Or, as some described him, an intelligent sociopath.

Starting from the age of 16, he was constantly in trouble with the law and in and out of jail. At first, it was car theft but it soon graduated to armed robbery. When a sentence of five years to life consigned him to Folsom State Prison in his early 20s, he only served the minimum before being released in December 1947. As events transpired, that wasn’t a lucky break.

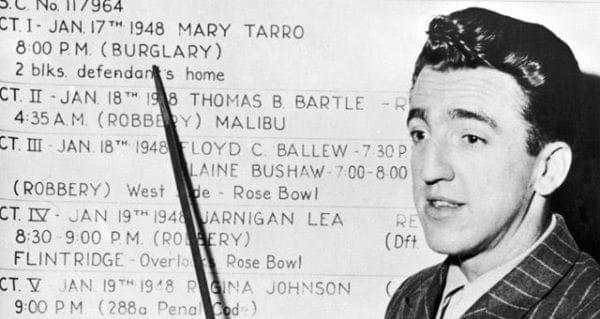

In January 1948, Los Angeles was afflicted by what the newspapers dubbed the Red Light Bandit. Preying on parked cars, the bandit’s modus operandi was to flash a red light resembling police practice, approach the cars and rob the occupants. On two occasions, women were removed and sexually assaulted.

Arrested after a high-speed car chase prompted by a clothing store robbery, Chessman confessed. He then disowned the confession, asserting that it was beaten out of him.

However, both Regina Johnson, 22, and Alice Meza, 17, the rape victims, identified him during the subsequent trial, at which he foolishly insisted on acting as his own lawyer.

Although Chessman wasn’t accused of killing anyone, he attracted the death penalty by virtue of California’s “Little Lindbergh Law.” The law, passed in the aftermath of the notorious 1930s kidnapping of aviator Charles Lindbergh’s infant son, specified that kidnapping with bodily harm was a capital offence. Moving the women to his car was defined as kidnapping and the sexual assaults were considered bodily harm.

If Chessman did himself no favours by self-representing at trial, he quickly became adept at drafting appeals to stave off execution. He also wrote the best-selling Cell 2455, Death Row (1954), which transformed him into an international cause celebre. By 1960, a long list of well-known people were pressing his case. Even Brigitte Bardot, then at the height of her cinematic sex kitten fame, got involved.

Right to the end, Chessman maintained his innocence. Yes, he acknowledged, he was a habitual criminal but not the Red Light Bandit. He also said that he knew the bandit’s identity. However, he wouldn’t disclose it.

Many of Chessman’s partisans professed to believe in his innocence or at least to argue the case for reasonable doubt. As an Irish teenager who became passionately immersed in the issue, I certainly did. It made for some lively discussions at home.

My mother would have none of it. As far as she was concerned, his execution was good riddance.

My father, although skeptical of Chessman, was ambivalent. He wouldn’t have been unhappy to see the sentence commuted but was unimpressed by many of the arguments made.

When I complained about the inhumanity of keeping a person on death row for almost 12 years, he pointed out that it was Chessman’s continued appeals and legal manoeuvring that extended the process. California would have been pleased to be done with him in 1948.

As for the argument about the macabre ritual surrounding executions, he asked what the alternative might be. Should someone just rush into the condemned man’s cell in the dead of night and bludgeon him to death?

Viewed rationally, it came down to questions of guilt or innocence, mitigating circumstances, whether the punishment fitted the crime, the application of the law and the appropriateness of capital punishment in any situation.

California Gov. Pat Brown wrestled with this dilemma, struggling to find a way to commute the sentence while abiding by the law. He failed.

Years later, Brown had this to say about Chessman: “He was a nasty, arrogant and unrepentant man, almost certainly guilty of the crimes he was convicted of, but I didn’t think those crimes deserved the death penalty then and I don’t think so now.”

Pat Murphy casts a history buff’s eye at the goings-on in our world. Never cynical – well, perhaps just a little bit.

The views, opinions and positions expressed by columnists and contributors are the author’s alone. They do not inherently or expressly reflect the views, opinions and/or positions of our publication.