I recently came across a gem on the Turner Classic Movies schedule. Called Primary, it’s a 1960 documentary.

I recently came across a gem on the Turner Classic Movies schedule. Called Primary, it’s a 1960 documentary.

The film is ostensibly a fly-on-the-wall record of the final days of Wisconsin’s 1960 Democratic presidential primary. In an era with far fewer such contests, it pitted U.S. Sen. John F. Kennedy of Massachusetts against U.S. Sen. Hubert Humphrey of Minnesota.

Wisconsin 1960 was seen as the first serious test of Kennedy’s viability. Would the glamorous media favourite play in the American heartland? Or would he melt along with Wisconsin’s receding winter snow?

Thanks to the recent evolution of lightweight portable equipment, the filmmakers were able to follow the two men during the campaign’s last five days. And the deal was that they’d simply record what was happening. There’d be no retakes or staged scenarios.

Of course, Kennedy and Humphrey were smart, savvy operators. So we can reasonably assume they weren’t oblivious to the cameras and that their behaviour and language reflected that awareness.

Still, what comes across is fascinating. It’s a close-up look at the two men going about the business of personally interacting with voters. And it’s also a window into a world that’s long gone – a simpler, less frenetic time without 24/seven news coverage, social media and elaborate security details.

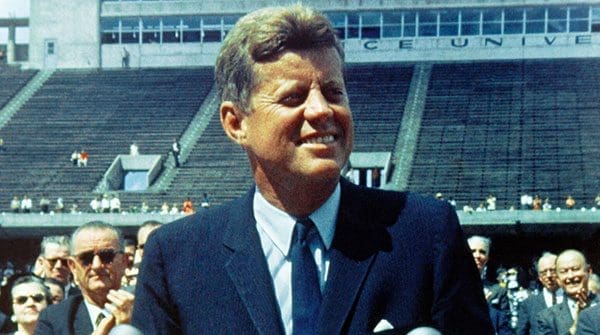

My prior memory of Kennedy footage comes from set speeches, debate clips and waving to crowds. This film’s perspective is different, offering a more intimate view that underlines just how charming Kennedy could be.

Gifted with matinee idol looks and a full head of hair, he exudes a grace and ease that few of his subsequent imitators could ever hope to match. But there’s also a sense of cool detachment, someone whose internal calculus was forever keeping score.

Humphrey, too, is a bit of a revelation, quite different from what I remember from his later campaigns in 1968 and 1972.

In 1968, he was Lyndon Johnson’s embattled vice-president, vainly struggling to get out from under the burden of the Vietnam War. Four years later, he was yesterday’s man, futilely attempting to reclaim his position in a Democratic Party that had moved on.

And in both of those campaigns, he seemed long-winded and garrulous. Indeed, his wife reputedly advised him that “a speech doesn’t have to be eternal to be immortal.”

The 1960 film, however, shows an additional side to Humphrey. Whether wooing voters on small town Wisconsin streets, addressing the issues near and dear to farmers, or taking crisp command of the preparations for a television call-in, he impresses as a politician not to be trifled with.

Physically, though, Humphrey appears at a disadvantage.

Shorter and rounder than Kennedy, he looks older and dowdier. It’s an impression further accentuated by his receding hairline and old-fashioned hat.

In reality, there was only six years between the two men. But while Kennedy projects an image of sleek modernity, Humphrey seems stuck in an earlier age.

Although the film doesn’t show it, the Kennedy operation played hardball. And charm notwithstanding, Kennedy could be ruthless in reminding people of the consequences for crossing him.

Being the more liberal of the two, Humphrey had a reasonable expectation of being endorsed by Wisconsin’s union leadership. Kennedy had no such hopes but he knew how to cut his losses.

Bluntly, Kennedy reminded the Milwaukee County Labor Council that supporting Humphrey wouldn’t be in their interest: “I sit on the Senate Labor Committee, and whether I win or lose, I will be in a position to work with you people.”

Humphrey didn’t get the endorsement.

Kennedy went into Wisconsin with high expectations. A January reading by his private pollster had pegged him at 63 percent of the vote. And shortly before the April 5 primary, he privately guessed he’d win nine of the 10 congressional districts.

Election night was a good deal more ambivalent than that.

Rather than 63-37, his popular vote margin was 56-44. And he only won six districts.

Naturally, the campaign operatives tried to spin the outcome. But nobody was fooled, least of all Kennedy.

When his sister asked him what it all meant, his response was devoid of wishful thinking: “It means that we’ve got to go to West Virginia in the morning and do it all over again.”

And so he did.

Pat Murphy casts a history buff’s eye at the goings-on in our world. Never cynical – well perhaps a little bit.

The views, opinions and positions expressed by columnists and contributors are the author’s alone. They do not inherently or expressly reflect the views, opinions and/or positions of our publication.