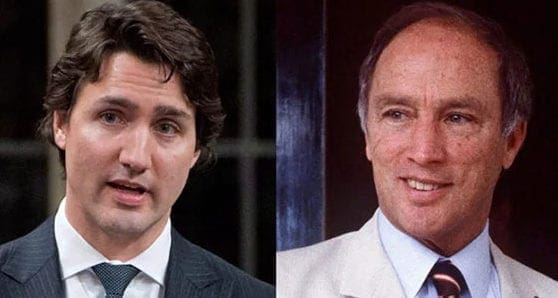

Some of the chatter around the federal election focused on the potential comparison between Justin Trudeau in 2019 and his father, Pierre Trudeau, in 1972. Given the circumstances – both men running to defend convincing majorities won four years earlier – it was an obvious topic.

Some of the chatter around the federal election focused on the potential comparison between Justin Trudeau in 2019 and his father, Pierre Trudeau, in 1972. Given the circumstances – both men running to defend convincing majorities won four years earlier – it was an obvious topic.

I wrote a column on it last January, specifically wondering whether the son’s fate would be similar to his father’s. Would comfortable majority turn into precarious minority, just as it surprisingly did in 1972?

It wasn’t a column I’d expected to write.

When Justin Trudeau was elected prime minister in 2015, I thought his popularity might have greater resilience than that of his father. It wasn’t a question of being a better leader, but rather of having a public personality with far fewer sharp edges.

Whereas people were initially dazzled by Pierre Trudeau’s charisma, intellect and strength, it wasn’t long before the accompanying arrogance and sense of moral superiority shone through. And this put a significant number of people off.

Having someone who doesn’t suffer fools gladly sounds fine until you realize that his definition of a fool tends to include anyone who disagrees with him.

In contrast to his father, I thought Justin Trudeau was largely free of these unattractive qualities. Or would at least hide them better. I was wrong.

So now that the results are in, how do father and son compare?

The things they have in common

Both men lost their majorities.

In Justin Trudeau’s case, his seat haul went from 54 percent to 46 percent of the total. His father’s seat loss was sharper, falling from 58 percent to 41 percent.

Both also experienced significant erosion in popular vote share, dropping between six and seven points. There is, however, a significant difference.

While Pierre Trudeau’s popular vote total ran between three and four points ahead of his nearest rival, his son came in almost a quarter-million votes behind. He was only saved on the seat side by a very efficient geographical vote distribution.

Finally, both men benefited from relatively lacklustre opposition.

For all his retrospectively ascribed virtues, Robert Stanfield was never going to light any political fires in 1972. And neither is today’s Andrew Scheer. This may not be fair, but fairness has nothing to do with it.

The differences

One of the things that’s different is the declining Liberal reliance on Quebec.

The province saved Pierre Trudeau’s bacon in 1972, giving him 56 of its 74 seats, which was just over half of his national total. Without Quebec, his pencil-slim two seat plurality would have disappeared and he’d have been unceremoniously turfed from office.

Indeed, consider a scenario where Quebec’s votes – for whomever they may have been cast – are excised from the national picture.

Pierre Trudeau’s political career would have been very different. While he’d still have scored a modest majority at the height of 1968’s Trudeaumania, he’d never have won another national election. His political reliance on Quebec was that profound.

Thanks to a pattern shift that began in the Jean Chretien era, Justin Trudeau doesn’t have the same dependence. Absent Quebec, he’d have 122 seats in a 260 seat house rather than 157 in a 338 seat house. That’s not much of a change in relative position.

There’s also a subtle difference in the two men’s minority governance situations.

Pierre Trudeau needed the support of a resurgent New Democratic Party (NDP). Having gained seats on a “corporate welfare bums” theme, they had the parliamentary votes to make legislation possible and the chutzpah to push their case.

Justin Trudeau, too, will need third-party support and the NDP is an obvious possibility. He does, though, have another practical option. Courtesy of the Bloc Quebecois resurgence, there’s a handy pool of votes to fish in on an issue-by-issue basis.

The Bloc may be separatist and Justin’s father may have been separatism’s arch-enemy, but there are deals to be made on other topics. Only the naïve would think otherwise.

And besides, the NDP had a poor night. Despite the many plaudits for leader Jagmeet Singh’s performance, the party’s Quebec collapse meant that it lost nearly half of its seats and around 20 percent of its vote share. That isn’t indicative of a party with intimidating big guns to deploy.

So what’s the bottom line? Is it yes or no to like father, like son?

Maybe it’s a bit of both.

Pat Murphy casts a history buff’s eye at the goings-on in our world. Never cynical – well perhaps a little bit.

The views, opinions and positions expressed by columnists and contributors are the author’s alone. They do not inherently or expressly reflect the views, opinions and/or positions of our publication.