The term ‘Islamophobia’ represents a refusal to reckon with the dangers of political Islamism in the name of “anti-racism”

It’s been just over six months since the Oct. 7 attacks on Israeli soil, and the debate around Islamism has returned to Western political discourse – along with the accusation of ‘Islamophobia’ repeatedly and callously hurled.

It’s been just over six months since the Oct. 7 attacks on Israeli soil, and the debate around Islamism has returned to Western political discourse – along with the accusation of ‘Islamophobia’ repeatedly and callously hurled.

Islamism refers to a political ideology that seeks to establish Islamic principles and laws within a society, often through the implementation of Sharia (Islamic law). It encompasses a wide range of beliefs and practices but generally involves advocating for the integration of Islam into all aspects of public and private life, including governance, law, education, and social norms.

For instance, in the wake of the attacks on Jews, schools across Canada have been urged to address and remedy not anti-Semitism but ‘Islamophobia.’ Similarly, at the beginning of Ramadan this year, Amira Elghawaby, Canada’s Special Representative on Combating Islamophobia, stated: “Muslims in Canada are particularly impacted by the war in Gaza, which has caused continuous anguish and sorrow within our diverse communities.”

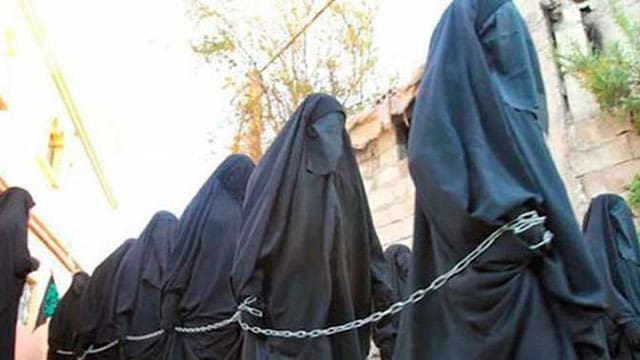

The blanket charge of ‘Islamophobia,’ instead of being used to repudiate bigotry against Muslims, has seemingly become a blunt instrument in silencing discourse on the dangers that political Islam poses to free speech and the values held by free societies. Critically, in some cases, this danger can even result in the tragic loss of life.

|

| Related Stories |

| Is there any hope of defeating antisemitism and politicized Islam?

|

| Exploring the origin of women’s lack of rights in Islam

|

| Jewish Canadians deserve the support of Muslim Canadians

|

On the morning of Nov. 2, 2004, the Dutch filmmaker Theo van Gogh was cycling to his production studio in Amsterdam when Muhammad Bouyeri approached van Gogh and shot him several times. Van Gogh fell off his bike and collapsed down the road. His last words were a desperate plea to the killer: “Can’t we talk about this?” Bouyeri then shot van Gogh four more times, took one of his butcher knives to the victim’s throat, and stabbed the other knife into his chest, bearing a five-page letter. The letter was addressed to Ayaan Hirsi Ali, a Somalian immigrant who was then serving as a member of the Dutch Parliament.

Two months prior, he and Hirsi Ali collaborated on a short film titled Submission, Part 1. The 11-minute short features a nameless woman in dialogue with Allah. She represents women who have been abused in the name of the Islamic faith, including Hirsi Ali herself. Written on the nameless woman’s body are Quran verses highlighting the unequal status of men and women under Islam.

Two years prior, a prominent Dutch politician, Pim Fortuyn, was gunned down in a car park after giving an interview on talk radio; it was the first political assassination on Dutch soil in 400 years. Of note, Fortuyn was openly gay, a supporter of gay rights, and highly vocal in his criticisms of Islamism. He saw in political Islamism a system of oppression against those who share his sexual orientation. Routinely labelled as ‘far-right’ by his detractors, he fiercely rejected this libel. Sadly, the murderer claimed there was “no other way he could stop that danger than to kill [him], … [as he] saw in Fortuyn an increasing danger to, in particular, vulnerable sections of society.”

In a functioning free society, one can disagree with people like van Gogh, Hirsi Ali, or Fortuyn without taking up arms and aiming for their lives. But not for a political Islamist, or a sympathizer of Islamism (like Fortuyn’s killer), where force is clearly considered an option.

Hence, the naivety of the ‘Islamophobia’ charge. For all intents and purposes, it represents a refusal to reckon with the dangers of political Islamism in the name of “anti-racism.” It is time we all ask: “Can’t we talk about this?”

As long as we refuse to learn from the tragic deaths of van Gogh and Fortuyn, in addition to the tireless warnings of Hirsi Ali, public discourse will be in even graver danger than it already is.

Chuong Nguyen is a research associate with the Aristotle Foundation for Public Policy and a Canadian expat and graduate student in American Studies at the Eötvös Loránd University (ELTE) in Budapest, Hungary.

For interview requests, click here.

The opinions expressed by our columnists and contributors are theirs alone and do not inherently or expressly reflect the views of our publication.

© Troy Media

Troy Media is an editorial content provider to media outlets and its own hosted community news outlets across Canada.