Things have taken a strange turn in Canada on the genocide front. Genocide? Canada? Those are words that you would not normally see together. Words like “polite” or “peaceful” might come to mind. But “genocide,” not so much. In fact, the picture of placid Canadians as practitioners of genocide is downright disturbing.

Things have taken a strange turn in Canada on the genocide front. Genocide? Canada? Those are words that you would not normally see together. Words like “polite” or “peaceful” might come to mind. But “genocide,” not so much. In fact, the picture of placid Canadians as practitioners of genocide is downright disturbing.

But that is the zombie movie playing out in the frozen north right now. The country is in some kind of existential, navel-gazing angst. Canada seems determined to confess to committing a genocide that never happened. I refer to the current frenzy to find the burial places of thousands of Indigenous children who supposedly left their parents’ homes to attend residential schools and “never returned.” Now, from coast to coast, ground-penetrating radar machines are being hauled around the country searching for the “thousands of missing children” who were never missing in the first place.

As the legitimate search for the burial places of students of Native American boarding schools gathers momentum, perhaps Americans should take note.

Because once extreme claims, like “genocide,” are accepted, bad things happen. In Canada, last summer, anti-Catholic bigotry stemming from the “genocide” claim reached such levels that 48 Catholic churches were set on fire.

The original mistake to accept the false claim of genocide was made by no less than Canada’s Prime Minister, Justin Trudeau. An advocate-run missing Indigenous women’s inquiry demanded that he accept their preposterous finding that Canada was committing ongoing genocide against Indigenous women – despite clear evidence that Indigenous men were overwhelmingly the perpetrators of that violence. Trudeau made the regrettable decision to give in to that unreasonable demand.

We must face up to Canada’s dark past by Gerry Chidiac

Telling our Indigenous people to ‘get over it’ comes dangerously close to outright genocide denial

That encouraged activists intent on extracting the maximum amount of money and political advantage from the genocide canard.

This past summer came the sensational claim that 215 bodies had been found in a mass grave at Kamloops, British Columbia. These were, according to the claim, children who had somehow died under mysterious circumstances or were even murdered and secretly buried, with the forced help of their fellow students – “some as young as six.”

And what was the evidence supporting this claim? It was from people known as “knowledge keepers” who purportedly had a “special way of knowing” and a junior anthropologist who had used a portable radar device – with the “knowledge keepers” telling her where to look. There were no bodies, just “soil disturbances.” Despite the weakness of this evidence, the media presented it to Canadians as proof of genocide.

An example of this “special way of knowing” is this: one knowledge keeper declared that “in 1500 the Pope decreed that all non-Catholic children at residential schools should be put to death.” Never mind that there were no residential schools in 1500 in Canada or that no Pope had ever made such a decree. That example says everything you need to know about her “way of knowing.”

At this point, one would have expected a number of things to happen. In the first place, you would expect journalists to closely question this astounding claim made on such incredibly flimsy evidence. Secondly, you would expect both government and church spokespeople to vigorously push back against such explosive and impossible statements with the facts.

But none of that happened. Quite the reverse. The government went into mourning and immediately showered Indigenous communities with money – communities that suddenly remembered all sort of similar stories of secret burials – to the point where $320 million has been made available to Indigenous communities that advanced claims.

Not surprisingly, Indigenous communities were quick to take advantage of this financial bonanza. An example is Marieval, Saskatchewan, where a project that began in 2019 as a routine community cemetery project was suddenly declared to be another “shocking discovery.”

The claims of thousands of “missing children” are false. Children died from disease at residential schools a hundred plus years ago, as they died on their home reserves. In fact, children died in cities and towns from disease in those days as well. It is true that, for many reasons, the death rate for Indigenous people was many times higher than for the mainstream. But it is not true that the death rate at residential schools was higher than it was on the reserves. And there is no credible evidence that children were murdered by priests, secretly buried at night, or any of the other Internet memes making their way through communities.

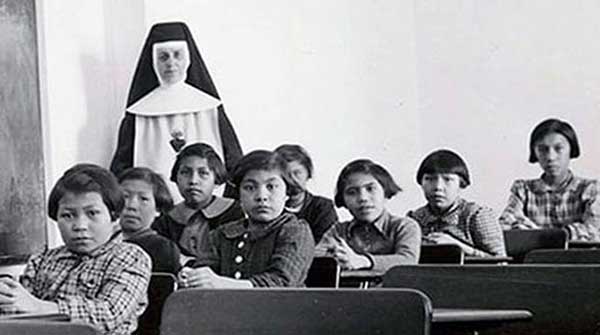

Canada’s residential schools experiment was a clumsy attempt at education. Many people were hurt. Those people deserve the compensation and apologies they received. But many others received educations that helped them live rich lives. While acknowledging the harm done, let’s remember the thousands of selfless nuns, priests and teachers who dedicated their lives to serving those needy Indigenous children – including many orphans and other destitute children. Many are buried next to the children they served.

It is unfortunate that the money incentives built into the fiasco that Canada’s residential school compensation process has become keeps the money claims – ever more extreme – coming in. The federal government and human greed let us down, and everyone is paying a heavy price for those mistakes.

But, there was no genocide. And Justin Trudeau does not speak for me, or, I think, most Canadians, when he says that Canada is guilty of genocide.

It is time for Canada to move on.

Brian Giesbrecht, retired judge, is a senior fellow at the Frontier Centre for Public Policy, an independent think tank based in Winnipeg, Canada.

Brian is a Troy Media contributor. For interview requests, click here.

The opinions expressed by our columnists and contributors are theirs alone and do not inherently or expressly reflect the views of our publication.

© Troy Media

Troy Media is an editorial content provider to media outlets and its own hosted community news outlets across Canada.