Think of the name Chamberlain and the person who springs to mind is the hapless Neville Chamberlain, the man who is – perhaps unfairly – remembered as the appeaser of Adolf Hitler. But he wasn’t the first Chamberlain to make his mark on British politics.

Think of the name Chamberlain and the person who springs to mind is the hapless Neville Chamberlain, the man who is – perhaps unfairly – remembered as the appeaser of Adolf Hitler. But he wasn’t the first Chamberlain to make his mark on British politics.

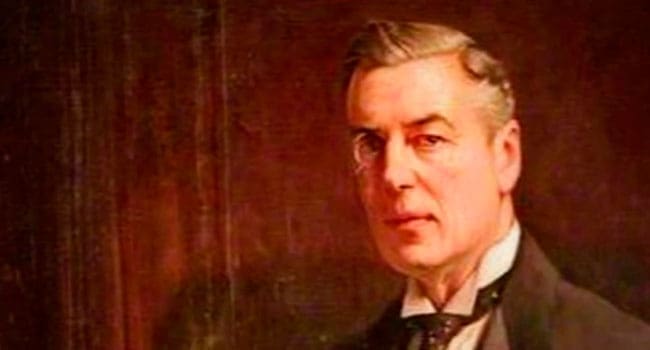

A generation earlier, Neville’s father cast a long shadow. Joseph Chamberlain – or Radical Joe as he was known – earned the distinction of being the man who split two political parties. Not many have managed to do that.

Joseph Chamberlain (1836-1914) came from a prosperously devout Unitarian family. His father was a London footwear manufacturer, into which business the young Joe ventured at the age of 16. Two years later, he was dispatched to Birmingham to look after the family’s interest in a screw manufacturing company.

Smart, energetic and innovative, Chamberlain was a great business success, so much so that he could afford to retire before turning 40. But it wasn’t a life of leisure that attracted him. Instead, he turned to politics.

After initial turns as a Birmingham city councillor and school board member, Chamberlain was elected mayor in 1873. Predictably, he was an activist incumbent.

| MORE IN BOOKS | |

| John F. Kennedy: an anglophile for all seasons By Pat Murphy |

|

| Two women defined by and celebrated for a single book each By Pat Murphy |

|

| Fenians used Canada as an Irish revolutionary pawn By Pat Murphy |

Gas, water and sewage were brought under municipal control; urban sanitation became a hot topic; slums were cleared; and libraries, schools and swimming pools were built. Biographer Peter Marsh summarises Chamberlain’s mayoralty this way: “Under his guidance Birmingham was known as the best governed city in the industrial world.”

But a man of Chamberlain’s energy and ambition wasn’t going to be satisfied with the municipal stage. So he was elected to parliament as a Liberal in 1876, and was in cabinet by 1880.

Although personally wealthy, Chamberlain was viewed as a radical, and the forthrightness with which he expressed his views caused ripples of discomfort. For instance, these words from an 1885 speech raised eyebrows: “I think in future we shall hear a great deal more about the obligations of property, and we shall not hear quite so much about its rights.”

There was, however, an interesting twist. Like some other Victorian-era radicals, Chamberlain was also an imperialist.

Ireland was the first flashpoint.

While Chamberlain’s inclinations towards Ireland were reformist, he drew the line at supporting the Liberal government’s 1886 Home Rule Bill. By providing Ireland with its own separate parliament, he believed the bill would dilute the power of Westminster and perhaps presage the breakup of the United Kingdom, of which Ireland was then a part.

Accordingly, he resigned from cabinet, thus precipitating an acrimonious split in the Liberal Party. It was to cost them not only the ensuing election but also their “natural governing party” status.

But it wasn’t the end of Chamberlain’s career. As a breakaway Liberal Unionist, he did business with the now dominant Conservatives, entering cabinet in 1895.

Interestingly, although he could have chosen to be Chancellor of the Exchequer or Home Secretary, Chamberlain opted for the until then lesser role of Colonial Secretary. Once there, his imperial vision took flight. “It is not enough,” he said, “to occupy great spaces of the world’s surface unless you can make the best of them. It is the duty of a landlord to develop his estate.”

Part of this vision entailed the creation of an imperial federation, politically and economically integrating the U.K. with the likes of Canada, Australia and New Zealand. Just as Canada had a federal parliament sitting in Ottawa, there’d be an imperial parliament at Westminster with representatives from the self-governing dominions.

Indeed, it was an element of this idea that precipitated his second party-splitting episode. This time, it was the Conservatives who felt the sting when Chamberlain quit the cabinet in 1903 to unsuccessfully campaign for the introduction of an imperial trade preference regime. Had it been adopted, the U.K. would have abandoned decades of free trade in favour of an imperial customs union.

Despite being partially incapacitated by a 1906 stroke, Chamberlain remained his own man until his death in 1914. And true to his spirit, his family refused the offer of a Westminster Abbey funeral, opting instead for Birmingham’s Church of the Messiah.

Now, more than a century later, the new British Tory prime minister is apparently an admirer of the urban reforming Radical Joe. It’ll be interesting to see how that admiration plays out.

Pat Murphy casts a history buff’s eye at the goings-on in our world. Never cynical – well perhaps a little bit.

The views, opinions and positions expressed by columnists and contributors are the author’s alone. They do not inherently or expressly reflect the views, opinions and/or positions of our publication.