I was a first-year university student in Dublin, Ireland, during the October 1962 Cuban Missile Crisis. But I don’t remember it as a time of great angst or agitation.

I was a first-year university student in Dublin, Ireland, during the October 1962 Cuban Missile Crisis. But I don’t remember it as a time of great angst or agitation.

True, the crisis dominated the news and there were certainly people who genuinely feared that nuclear Armageddon was on the doorstep. However, the daily life of the broad society went on as usual, and university activities were consumed with the normal business of attending lectures, grappling with essay assignments and attending the weekend student dance.

What explains the apparent stoicism?

It was, of course, an era without social media, so the ability to generate mass emotion was far more constrained than it is today. And we were still several years away from the culture of student demonstrations as a regular feature of university life.

|

| Related Stories |

| The Bay of Pigs fiasco upended J.F.K.’s presidential honeymoon

|

| J.F.K. dug a deep hole in his relationship with Khrushchev

|

| When Khrushchev spilled the beans |

But there was more to it than that.

In Ireland, John F. Kennedy was close to being a secular saint. People generally took great pride in the fact that an Irish-American Catholic had ascended to the U.S. presidency. And the combination of Kennedy’s youth, style and charisma compounded the admiration. He was a romantic hero who could do no wrong.

Consequently, Kennedy’s decision to confront the Soviets over missiles in Cuba must be justified. It was no time for queasiness or second-guessing.

Conventional wisdom had also adopted the view that appeasement was a bad thing. If Neville Chamberlain had resisted Adolf Hitler in Munich in 1938, perhaps the grotesque carnage of the Second World War would’ve been avoided. Dictators should never be allowed to have their way.

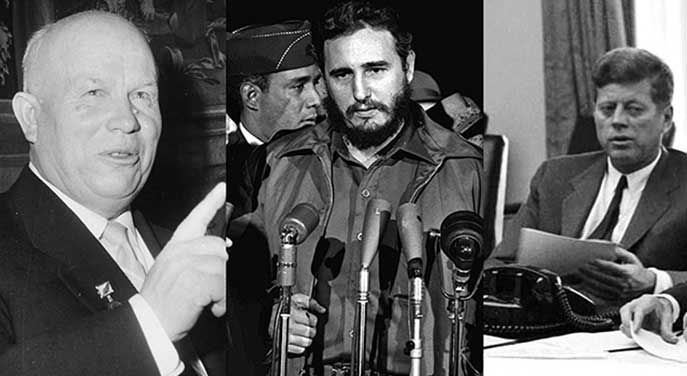

And Kennedy had come to power as a man who’d stand up to the Soviets and their leader Nikita Khrushchev. In geopolitical parlance, he was a Cold Warrior. Unfortunately, he didn’t make a good first impression.

Shortly after he took office, there was the fiasco of the April 1961 Bay of Pigs invasion, the failed American-sponsored attempt to overthrow Cuban dictator Fidel Castro. This was followed a couple of months later by the unfortunate summit conference in Vienna where, as Kennedy privately complained, he was treated “like a little boy.”

From these events, Khrushchev formed an unflattering opinion. Kennedy was, in his assessment, “Too intelligent and too weak.”

Emboldened by this impression, the Soviet leader set about solving two problems.

One problem was protecting his ally Castro from any further American overthrow attempts. And the other was rectifying the nuclear imbalance.

To quote historian Rodric Braithwaite: “The Americans had over 1,500 nuclear bombers, and a ring of bases surrounding the Soviet Union from which they could hit Moscow. The Russians only had 150 long-range bombers, a few clumsy long-range missiles and nothing that could reliably hit Washington.”

Khrushchev’s solution was conceptually simple.

He’d secretly send nuclear missiles and bombers to Cuba, along with ground troops. Once these were all in place, Cuba would be protected and the Soviets would have a capability to hit the American mainland roughly equivalent to the American capability to hit the Soviet Union. It would be a fait accompli that Washington could do nothing about.

But American spy planes discovered what was going on before the plan was fully executed. And what followed was the 13 tense days of crisis, which included an American naval quarantine of Cuba designed to turn back Soviet ships carrying missiles. The world seemed to hover on the brink.

When it was over, the narrative that emerged was one of American triumph. In the words of secretary of state Dean Rusk, “We’re eyeball to eyeball, and I think the other fellow just blinked.” Kennedy had stared down Khrushchev to win the day.

The reality was somewhat more complicated. There had been a deal.

Khrushchev agreed to withdraw his missiles and troops from Cuba in return for Kennedy’s promise to forego any future invasions of the island and to dismantle the American intermediate-range missiles in Turkey. That last bit, however, wasn’t publicly disclosed.

Indeed, historian Sheldon Stern notes that the missile-swap secret was even kept from Kennedy’s vice-president – and subsequent successor – Lyndon Johnson. He puts it this way: “Johnson went to his grave in 1973 believing that his predecessor had threatened the use of U.S. military power to successfully force the Soviet Union to back down.”

One wonders to what extent, if any, this misapprehension influenced Johnson’s futile policy in Vietnam.

Pat Murphy casts a history buff’s eye at the goings-on in our world. Never cynical – well, perhaps a little bit.

For interview requests, click here.

The opinions expressed by our columnists and contributors are theirs alone and do not inherently or expressly reflect the views of our publication.

© Troy Media

Troy Media is an editorial content provider to media outlets and its own hosted community news outlets across Canada.