On Dec. 31, as Canada was about to inaugurate its 150th year, some sharp-eyed reporters noticed something wrong: the prime minister was absent. Where was Justin Trudeau?

On Dec. 31, as Canada was about to inaugurate its 150th year, some sharp-eyed reporters noticed something wrong: the prime minister was absent. Where was Justin Trudeau?

He and his family were on a private island in the Caribbean visiting the Aga Khan.

Apart from criticizing the PM for missing the launch of this important national celebration, the media pounced on Trudeau personally – surely this vacation was proof that Trudeau cared more about his very rich friends than average Canadians.

Somewhat surprisingly, Trudeau’s initial reaction was defensive and apologetic. The Liberal leader seemed unaware that he had made a misstep.

Rather than going on the offensive, he reversed course, cancelling a trip to Switzerland (where he’d be hobnobbing with more rich folks) and hastily arranging a national tour to meet with ‘average’ Canadians.

But aside from the very Canadian desire for a winter sun break, what was the purpose of Trudeau’s holiday? More importantly, who is this Aga Khan fellow?

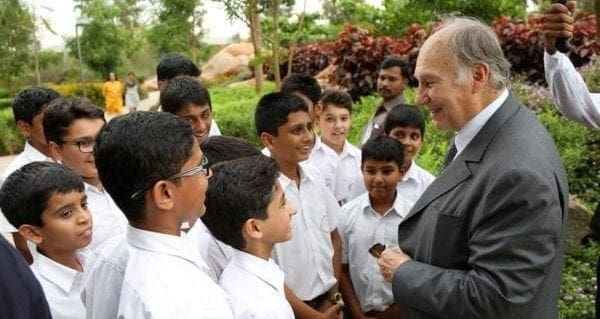

The Aga Khan is a prominent spiritual leader and an international businessman. He’s considered a direct descendent of the Prophet Muhammad and, consequently, head of a Shia Muslim sect known as the Ismaili.

The Aga Khan’s close relationship with Canada dates from the early 1970s when Justin Trudeau’s father, Pierre Trudeau, helped the Ismailis of Uganda find a new home in Canada when they were expelled by the brutal dictator Idi Amin.

The Aga Khan has also provided a vital bridge between Islam and the West.

In its golden age, Islam developed a highly refined civilization. Muslims of the Fatimid Caliphate (909 to 1171) were quite different from the image that Islam projects today. Islam then was a tolerant, business-friendly culture that developed remarkable scientists, such as Ibn al-Haytham, whose achievements include an early version of the camera and a systemized form of scientific method.

Ismailis played significant roles in this remarkable society; many were scientists, administrators or merchants, trading produce, silks, wines, olive oil and other commodities in commercial networks that stretched from India to the Atlantic coast of Iberia.

Many are surprised to learn that the foundations of western civilization were imported from Islam at this time. These imports included works of philosophy, important mathematical and scientific innovations, as well as some stunning works of art. One of the most important Islamic imports, Arabic numerals, were adopted by the West in the 14th century, rapidly accelerating the advance of western science and finance.

In addition to these civilizational achievements, the Fatimid Caliphate developed a highly complex and effective form of capitalism. They’re credited with establishing many free-market institutions, banking and corporate structures, as well as key accounting innovations that today underpin commercial capitalism.

The Aga Khan reminds the world that the violent and intolerant version of Islam, offered up by the Islamic State, is not the whole story.

Many modern Muslims living in the West question whether they can share western values and stay true to their religion. In fact, many western values and institutions originated within Islam – we have a lot in common, if only we knew more of our shared history.

The Ismailis are proof that an easy and productive relationship between the secular West and Islam is possible.

In the modern world, we tend to ignore relationships or the importance of building what many call relational capital. I’m sure the Trudeau family’s vacation had many pleasant side benefits. However, in maintaining close relations with the Aga Khan, the prime minister was simply doing his job, building the relational capital necessary to preserve the long-term peace and stability of a vibrant multicultural Canada.

Instead of criticizing Trudeau’s conduct, perhaps we should celebrate the fact that Canada is favoured by an Islam group that could unite what many consider incompatible civilizations. As we celebrate our nation’s 150th year, unity seems like a formidable theme.

Robert McGarvey is an economic historian and former managing director of Merlin Consulting, a London, U.K.-based consulting firm. Robert’s most recent book is Futuromics: A Guide to Thriving in Capitalism’s Third Wave.

Robert is a Troy Media contributor. Why aren’t you?

The views, opinions and positions expressed by columnists and contributors are the author’s alone. They do not inherently or expressly reflect the views, opinions and/or positions of our publication.