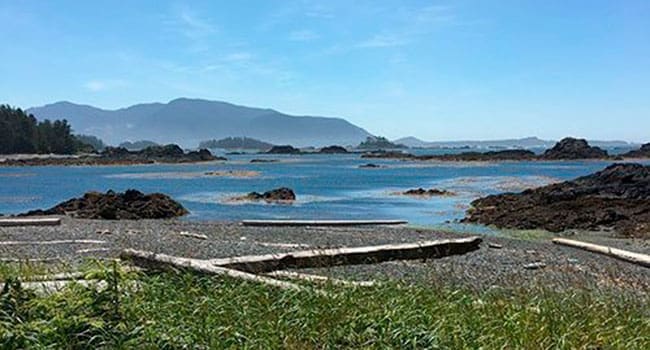

Nuchatlitz lagoon, framed by a formidable offshore wall of reefs and rocks, is sprinkled with small islands.

Nuchatlitz lagoon, framed by a formidable offshore wall of reefs and rocks, is sprinkled with small islands.

Consulting the Canadian Hydrographic Service chart entitled Esperanza Inlet, one is quickly puzzled by their odd place names. While Nuchatlitz Provincial Park and four IRs (Indian reserves) are prominently badged, the entire flotilla of Nuchatlitz islands (I counted 20) are mostly numbered – as in 37, 40, 34, 44, 36, 33 and so on – from north to south. We gradually came to conclude that this designation, the chart being metric, perhaps meant metres above high tide. The chart is silent on this matter, just as it is on the Nuu-chah-nulth indigenous place names that must exist for the area.

By just consulting the place names on the chart, the average tourist might fairly conclude that they were in southern Spain, the Royal Naval Academy map room, or a logging camp, instead of the west coast homeland of the Ehatisaht and Mowachaht. Catala Island, Bodega island, Espinosa Inlet, Lord Island, Jurassic Point, Products Creek, CeePeeCee and Log Dump have pride of place on the map.

However, once you are kayaking in the lagoon, the tyrannies of history melt away and one is enticed by the sublime beauty of the surroundings.

On our recent paddle through the lagoon, we were intrigued by a strange image in the binoculars on Island 37, some five km to the south of our camp on Island 40. The magnified image suggested a wrecked ketch, with two masts still standing in a whitened hull. The sailboat seemed beached on the high tide line and was bleached white.

After a big breakfast, we decided to paddle in the shelter of Mummucknee Island, which we had previously explored and named (on the chart it is conspicuously unnamed). We planned to attempt a protected entry to the southern extremity of the lagoon by heading south in the channel created by the adjacent IR island.

As it turned out, we hit the channel at a falling tide and had to yard the kayaks over a sandy berm to reach the open waters on the other side. From here, we rounded a no-named point and headed southeast with Island 37 some two km in front of us.

By now we were getting the lay of the land and waters. Inside the lagoon, in the protected waters of the offshore reef, it might as well have been Paul Theroux’s Happy Isles of Oceania. The hot summer sun beat down on our hat-covered heads and we travelled forward in anticipation on a waveless sea.

Island 37 soon drew closer and our shipwreck turned out to be two white tree trunks tipped vertically above a bleached log. We wondered if we had been pranked by a previous crew of lagoon pirates; somebody surely had crafted a marvellous illusion for the northern residents of Island 40.

We decided to have lunch on the island and pulled up our kayaks on another perfect canoe beach. Up above us in the forest were the telltale remnants of yet another Nuchatlitz house site: a cleared area slowly being reoccupied by coastal rainforest, a few crab apple trees hanging on for dear life and a shell midden of ancient clamshell meals, which in this part of the world could literally indicate several thousand years of continuous cultural occupancy.

As we ate our sandwiches, I wondered if each of the islands in the lagoon were family-owned. Were we kayaking through a multifamily village where for generations the residents had cultivated a unique pattern of insular residency, perhaps for defence?

I made a mental note to do some research on this idea when I returned to the sedentary world of books from the muscular world of paddle strokes.

Upon our return, I located the reference I was looking for, on page 228 of anthropologist Philip Drucker’s The Northern and Central Nootkan Tribes, published by the Bureau of American Ethnology in 1951. Drucker notes that the insular “discontinuity of Nuchatlet territory … indicates that the Nuchatlet confederacy was formed of the left-overs of the Moachat and Ehetisat unions. Groups who were displaced, and others whose safety may have been threatened, perhaps joined forces for common defence.”

The kayak anthropologist in me thinks he got it right. Nuchatlitz is a village of family islands united for mutual protection.

Mike Robinson has been CEO of three Canadian NGOs: the Arctic Institute of North America, the Glenbow Museum and the Bill Reid Gallery. Mike has chaired the national boards of Friends of the Earth, the David Suzuki Foundation, and the Canadian Parks and Wilderness Society. In 2004, he became a Member of the Order of Canada.

The views, opinions and positions expressed by columnists and contributors are the author’s alone. They do not inherently or expressly reflect the views, opinions and/or positions of our publication.