Watching the fraught state of Brexit negotiations brought Charles de Gaulle to mind.

Watching the fraught state of Brexit negotiations brought Charles de Gaulle to mind.

On Jan. 14, 1963, de Gaulle – in his capacity as president of France – publicly blocked Britain’s entry into what was then known as the common market.

“England,” he said, “is an island, sea-going, bound up by its trade, its markets, its food supplies, with the most varied and often the most distant countries.” As such, it didn’t fit his idea of a Europe-centric construction dominated by France.

And to make things worse, there was the spectre of the Americans. If the British were allowed into Europe, “there would emerge a colossal Atlantic community under American dependence and direction.” Wittingly or unwittingly, Britain would be an American Trojan horse.

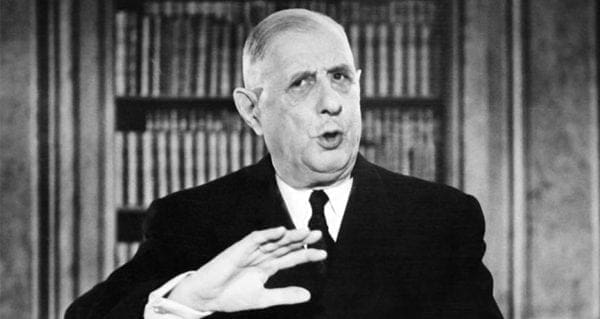

De Gaulle (1890-1970) was an unusual man. Solitary and arrogant, he had a great capacity to annoy people. But he also came to embody the spirit of France at two critical junctures.

One was the darkest days of the Second World War, when France was defeated, occupied and humiliated. The other was when he came out of retirement to take the reins of government as the Fourth Republic disintegrated in 1958.

De Gaulle’s concept of France has been described as heroic and history-steeped, even if the contents were selectively chosen. Writing a history of the French Army, he managed to omit Waterloo. A strong sense of national grandeur was important to him.

There was also a distinct streak of anglophobia. Speaking in 1962, de Gaulle put it this way: “Our greatest hereditary enemy was not Germany, it was England. From the Hundred Years War to Fashoda, she hardly ceased to struggle against us. … She wants to stop us succeeding with the common market. True, she was our ally during two world wars, but she is not naturally inclined to wish us well.”

Despite a long military career, de Gaulle was a relative unknown when he arrived in London on June 17, 1940. He didn’t bring much by way of possessions – just a couple of suitcases and “a handful of francs.” Neither did he have much facility with the English language. Later, he described his experience as being “alone and deprived of everything, like a man on the edge of an ocean that he was hoping to swim across.”

But de Gaulle had one thing going for him: the British needed someone to put forward as the voice of Free France and Winston Churchill decided to take a flyer on him.

So the following day, June 18, de Gaulle made the first of what was to be many BBC broadcasts to France. It was the beginning of the legend.

Although this British-facilitated role was the catalyst for de Gaulle’s subsequent fame, the wartime relationship wasn’t a happy one.

Wounded pride was one of the problems. Being grossly dependent didn’t fit well with de Gaulle’s personality or his conception of a glorious France. And being difficult to the point of intransigence was a means of coping with the pain.

In addition, de Gaulle was often kept in the dark with respect to planning, even when the operations – such as D-Day – directly pertained to France. The fact that the Americans didn’t care for him compounded the situation, leading to a memorably acrimonious exchange just prior to the invasion. An exasperated Churchill was unequivocal: “Any time I have to choose between you and (Franklin) Roosevelt, I will always choose Roosevelt.”

Post-war, the relationship shifted. Having initially kept the common market at arm’s length, Britain changed its mind and applied for membership. De Gaulle vetoed the application.

The British had two motivations.

One was the belief that Europe was a ready-made answer to Britain’s chronic economic underperformance. That was an illusion. Even after it was eventually admitted (post-de Gaulle) in 1973, Britain continued to struggle until the homegrown reforms of Margaret Thatcher took hold in the 1980s.

The other motivation had to do with finding a new world role, something to prevent Britain from receding into the relative obscurity of “a greater Sweden.” Looking towards Europe as a potential power platform, Labour Prime Minister Harold Wilson memorably observed, “If we can’t dominate that lot, there’s not much to be said for us.”

For all his foibles and manipulations, it’s hard to escape the conclusion that de Gaulle was basically right. Britain, or at least England, didn’t belong in Europe.

Pat Murphy casts a history buff’s eye at the goings-on in our world. Never cynical – well, perhaps just a little bit.

The views, opinions and positions expressed by columnists and contributors are the author’s alone. They do not inherently or expressly reflect the views, opinions and/or positions of our publication.