Grocers racked up millions of dollars in profits as they increased revenues during the first year of the pandemic. But numbers this year tell us tougher economic times await them.

And the economy is just one part of the story. Nobody really knows how the economy will look this fall and winter as a return to normalcy progresses.

To add to the confusion, few appreciate how the workforce will look as we exit the COVID-19 pandemic. Many will likely continue to work from home, part-time or full-time.

Where people spend their days matters a great deal to grocers and restaurant operators. For years, marketing gurus have stated that location is king. If you don’t know where people will work, this mantra’s importance is almost impossible to gauge.

According to Statistics Canada, about 69 percent of our food budget was spent on food bought at retail during the first quarter of 2021. The remaining 31 percent was spent at food service outlets. In April 2020, early in the first phase of lockdowns, food service represented barely nine percent of our food expenditure.

We should be back to a 65/35 split by the end of the year, if not sooner. People will become nomads again – at least for a while. By fall, we should have a better sense of how the economy holds together without the federal government’s substantial handouts. This is what our grocers are up against.

These factors are a given, but it was pointed out recently by Francis Parisien of NielsenIQ that the demographic fabric of our country is another factor starting to worry grocers. Canada has had one of the steadiest fertility rates of any developed country. But that rate was at 1.51 in 2020, far short of the 2.1 needed to maintain our population.

The decline is largely due to women playing a more meaningful role in our economy. Many more women are choosing to have fewer or no children. And the pandemic and its severe impact on young Canadians’ professional career paths appears to be accelerating this trend.

According to the United Nations report World Population Prospects, Canada’s birth rate could drop by up to four percent by 2026. It projects the birth rate to increase after that but we’re looking at a few years when many Canadians put baby plans on hold. It’s unclear how long this might last.

But it is clear that most young adults are trying to figure out their place in a post-pandemic world.

The effects of Canada’s modest birth rate were always offset by our open-door immigration policy. But in April of this year, Canada welcomed less than 22,000 new immigrants, the lowest monthly count this year. Canada aimed to welcome 341,000 new immigrants in 2020 but only managed to admit 184,000 due to COVID-19-related disruptions such as travel restrictions.

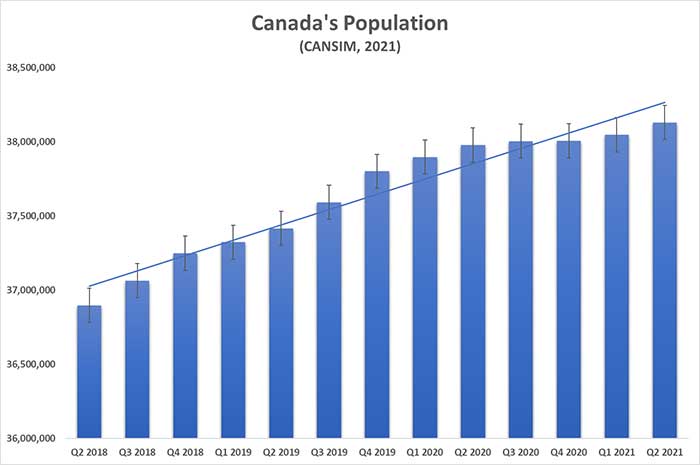

Canada’s current population is a little over 38 million, according to Statistics Canada. But over the last nine months, the country’s population growth was under our three-year trend average, going back to 2018. This also means our population’s average age could creep higher. For a grocer, that’s important information.

We did experience a population bump at the end of 2018, proving things can always turn around for us. But the pandemic has made most benchmarks completely useless.

In addition, immigrants tend to move to major urban centres. The pandemic made many people’s addresses less relevant and pushed many to leave their city homes. With fewer immigrants moving to cities and others moving out, maintaining stores in some markets will prove difficult. Expect conversions or even closures as parts of the Canadian market may have too many stores.

Canada is home to a little more than 15,000 grocery stores, and 19 percent of them employ over 50 people. That’s one store for every 2,500 Canadians. With higher food prices and sluggish population growth, grocers will be compelled to revisit their real estate portfolios.

The demographic cliff created by the pandemic will be a major obstacle for Canadian grocers as they try to grow. How they navigate through these challenges will be crucial.

Dr. Sylvain Charlebois is senior director of the agri-food analytics lab and a professor in food distribution and policy at Dalhousie University.

Sylvain is a Troy Media contributor. For interview requests, click here.

The views, opinions and positions expressed by columnists and contributors are the authors’ alone. They do not inherently or expressly reflect the views, opinions and/or positions of our publication.