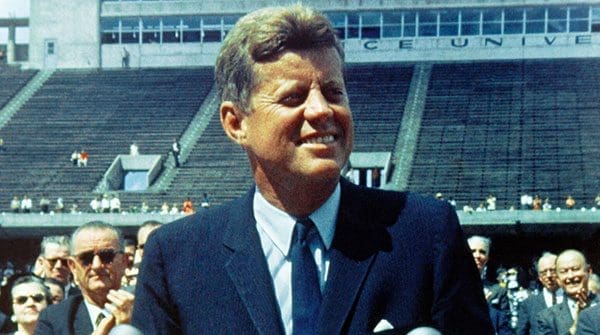

While adored as ‘one of us’ during his 1963 visit to Ireland, Kennedy had, by that time, become a global figure

U.S. President John F. Kennedy’s June 1963 visit to Ireland wasn’t his first time in the country. He’d been there twice before, once in 1945 and again two years later. But this was different. No longer an obscure Irish-American, he was now – as per the official welcome – “the first citizen of the great republic of the west, upon whose enlightened, wise and firm leadership hangs the hope of the world.”

U.S. President John F. Kennedy’s June 1963 visit to Ireland wasn’t his first time in the country. He’d been there twice before, once in 1945 and again two years later. But this was different. No longer an obscure Irish-American, he was now – as per the official welcome – “the first citizen of the great republic of the west, upon whose enlightened, wise and firm leadership hangs the hope of the world.”

To most Irish people, Kennedy was “one of us,” someone whose success reflected favourably on themselves. As the elderly Irish president put it, he was “a distinguished son of our race.” Being proud of him was to be proud of oneself.

Tens of thousands turned out to pay homage to the tanned, handsome figure whose very presence exuded political power and film star glamour. Journalist Fintan O’Toole has noted the “beatific bliss” on the faces of the crowds “pressing towards him as towards a messiah.” And there was even an eruption of hysteria when he was “literally mobbed” at a garden party for the great and the good.

Photo by History in HD |

| Related Stories |

| The Road to Camelot offers fresh insights into JFK mythology

|

| JFK and Reagan more alike than you’d think

|

| The CIA’s man in Cuba

|

Truth be told, though, Kennedy was no longer “one of us.” He’d moved beyond that. Way beyond.

It wasn’t a matter of Kennedy being in any way ashamed of his Irish Catholic heritage. By all accounts, he was completely comfortable with it. And, of course, he skilfully deployed it during his political rise. But it didn’t define who he was or how he perceived the world.

Take, for instance, the perennial grievance of Irish partition, which is generally a big thing for Irish-Americans. In an address at a 1954 New York St. Patrick’s Day dinner, Kennedy’s reticence on the subject caused one disappointed attendee to liken the experience to “eating your soup with a fork.”

Culturally and socially, Kennedy was more anglophile than son of Erin. And it showed up in the books he read, the people he admired, the friendships he made and the topics that engaged his interest.

One of his favourite books was The Young Melbourne, David Cecil’s biography of the 19th-century English politician William Lamb. As Lord Melbourne, Lamb had been the young Queen Victoria’s political tutor and first prime minister. For lighter stuff, Kennedy was keen on Ian Fleming’s James Bond.

Another Englishman, Winston Churchill, was Kennedy’s 20th-century hero, which was an interesting choice in light of the personal antipathy between Churchill and Kennedy’s father. In April 1963, he conferred honorary American citizenship on Churchill, the first foreigner to receive that acclaim.

But perhaps most important of all, there were the personal friendships and social relationships dating back to Kennedy’s sojourn at the London School of Economics in the mid-1930s. Certain aspects of English upper-class life caught his fancy. There were the lively political discussions, eccentric characters and visits to grand country houses, not to mention the parties with entertaining gossip and free-spirited women.

Anglophilia wasn’t the only respect in which the real Kennedy was at odds with his adoring Irish audience.

Although he’d briefly been an isolationist in his youth, Kennedy learned a particular lesson from the unfortunate denouement of 1930s appeasement, a lesson that informed his foreign policy perspective for the rest of his life. Aggression on the part of potential enemies should be resisted long before it directly threatened American shores. Thus, like many of his peers, Kennedy was a Cold Warrior who saw the Soviet Union as a mortal danger and American-led collective defense as the antidote.

Ireland, however, treasured its neutrality. Much to America’s post-Pearl Harbour chagrin, it had stayed out of the Second World War. And it wanted no truck with NATO.

Albeit not then in the public domain, there was also a material mismatch on sexual mores.

Public morality in the Ireland of 1963 was still deeply puritanical on all matters pertaining to sex. While often honoured in the breach, there was still strong social disapproval of extra-marital sex in any and all of its manifestations. But Kennedy, as we now know, could be described as the libertine’s libertine.

Irish president Eamon de Valera may have been 80 years old and afflicted with failing eyesight, but he was nobody’s fool. Reacting to the euphoria suggesting that Kennedy might establish a post-presidential residence in Ireland, de Valera privately observed that “there was no real sense of connection … what we saw was the president’s charm and good manners rising to the occasion, not him preparing the groundwork to live here.”

Unlike many of his countrymen, de Valera didn’t fall in love.

Troy Media columnist Pat Murphy casts a history buff’s eye at the goings-on in our world. Never cynical – well, perhaps a little bit.

For interview requests, click here.

The opinions expressed by our columnists and contributors are theirs alone and do not inherently or expressly reflect the views of our publication.

© Troy Media

Troy Media is an editorial content provider to media outlets and its own hosted community news outlets across Canada.