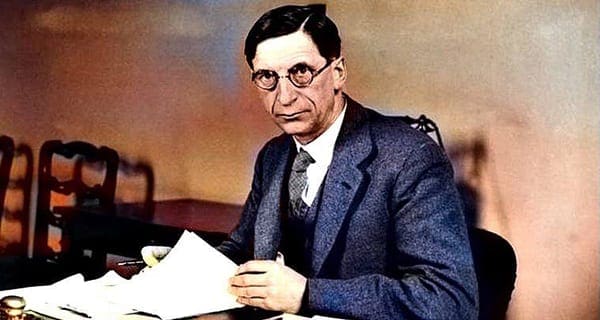

Eamon de Valera was a militant revolutionary, prime player in the Civil War and prime minister of Ireland for 21 years

The dominant Irish political figure of the 20th century died just 40 years ago. Born in New York but raised in Ireland by his maternal family, Eamon de Valera served as the equivalent of prime minister for 21 years between 1932 and 1959. Before that, he was a militant revolutionary during the Irish War of Independence and a prime player in the subsequent Civil War that followed the 1922 establishment of the Irish Free State.

The dominant Irish political figure of the 20th century died just 40 years ago. Born in New York but raised in Ireland by his maternal family, Eamon de Valera served as the equivalent of prime minister for 21 years between 1932 and 1959. Before that, he was a militant revolutionary during the Irish War of Independence and a prime player in the subsequent Civil War that followed the 1922 establishment of the Irish Free State.

To his many critics, Eamon de Valera was a devious man with blood on his hands, someone whose wilful manoeuvrings were instrumental in precipitating the bitter Civil War. To his more numerous admirers, he became the embodiment of Irish republican nationalism, the very heart and soul of mid-20th century puritanically Catholic Ireland.

Inward looking and underdeveloped, de Valera’s Ireland was an economically troubled place. But then again, economics wasn’t the thing that turned his crank. For him, the bigger issues revolved around promoting national consciousness, preserving and cultivating a distinctive Irish culture, and (futilely) attempting to resolve the perceived iniquity of partition – whereby the Protestant/Unionist majority in Northern Ireland had opted to remain in the United Kingdom rather than join the new Irish state.

It was a situation replete with contradiction. In an ethos dominated by the concept of the mystically unified Irish nation, a chronically underperforming economy compelled many to emigrate to, of all places, England! The historian Tom Garvin put it succinctly: “A huge Irish proletariat accumulated in Britain, building roads and infrastructure for the new Britain rather than for a new Ireland.”

Let’s be fair, though. While prime ministers and presidents can certainly tank an economy, they’re less potent on the upside. Where economic growth is concerned, many factors come into play and smart government is only one of them. Of course, this doesn’t mean that de Valera’s frugal self-sufficiency, protectionism and state-sponsored industries were necessarily a wise policy choice. But, by the same token, there was no magic wand lying around waiting to be waved.

One area of clear choice, however, was his decision to keep Ireland neutral during the Second World War. These days, that attracts a fair amount of moral criticism. How, it’s argued, could anyone stay aloof from the struggle against the evil that was Nazi Germany?

But then again, there’s a substantial element of Monday morning quarterbacking here. Quite apart from Ireland’s historical quarrels with Britain, what was morally clear in 1945 wasn’t necessarily so obvious in 1939. And let’s not forget that many countries that did get involved only did so after they’d been attacked. Retrospective rhetoric aside, pure self-preservation was often the order of the day.

Two other things require recognition in any serious assessment of de Valera’s legacy.

One was the preservation of Irish democracy during the turbulent 1930s. While much of Europe was embracing – or at least flirting with – fascism, de Valera resisted the temptation and actively stepped on anyone who demonstrated any such ambitions. And while he personally wrote much of the 1937 constitution, he refrained from using the opportunity to create a powerful executive that wasn’t answerable to parliament. As he privately put it, he was “too trained in English democracy” to go that route.

The other thing was the suppression of the Irish Republican Army (IRA) and its aspirations for exercising extra-parliamentary power. When the IRA murdered Irish policemen, de Valera executed the perpetrators. When IRA prisoners went on hunger strike, he let them die. Believing that intransigence feeds on concessions, he brooked no compromise with anyone who denied the legitimacy of the state. Decades later, Margaret Thatcher took the same view.

From the vantage point of the 21st century, it’s very easy to disparage de Valera and his world. Not being a fan of his, I’ve done so myself on occasion.

However, those of us who are critics need to reckon with the fact that he consistently won elections, so his perspectives and priorities obviously resonated with many. And while we may shake our heads at why people responded that way, they were who they were.

Eamon de Valera’s Ireland is dead and gone now, replaced by something which he’d find unrecognizable and of which he’d heartily disapprove. Mind you, Winston Churchill probably wouldn’t be too pleased with modern England either. History tends to work that way.

Pat Murphy casts a history buff’s eye at the goings-on in our world. Never cynical – well perhaps a little bit.

For interview requests, click here.

The opinions expressed by our columnists and contributors are theirs alone and do not inherently or expressly reflect the views of our publication.

© Troy Media

Troy Media is an editorial content provider to media outlets and its own hosted community news outlets across Canada.