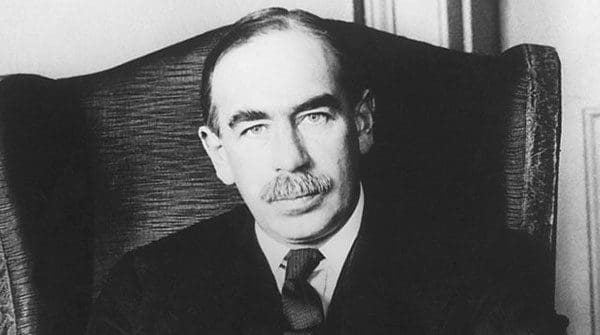

John Maynard Keynes and the rise, fall, and resurgence of his economic theory

When I was an economics undergraduate in the early 1960s, John Maynard Keynes was the big name in the field. His ideas were dominant, both in academia and the broader world of economic policymaking. The contemporaneous phrase “We’re all Keynesians now” neatly captured how the erstwhile radical had become conventional wisdom.

When I was an economics undergraduate in the early 1960s, John Maynard Keynes was the big name in the field. His ideas were dominant, both in academia and the broader world of economic policymaking. The contemporaneous phrase “We’re all Keynesians now” neatly captured how the erstwhile radical had become conventional wisdom.

Keynes was born in Cambridge, England, on June 5, 1883. His family circumstances can be characterized as upper-middle-class, his father being an economist and lecturer at the university there. And Keynes himself took to the intellectual life, earning a mathematics BA in 1904, publishing his first economics article in 1909 and his first book in 1913. Although he never took a formal economics degree, in one form or another it was a subject that came to define his life and reputation.

John Maynard Keynes |

| Related Stories |

| Why Milton Friedman’s ideas still resonate

|

| Modern monetary theory was too good to be true

|

| An economist who put the accent on compassion

|

Keynes wrote prolifically, not just books but also articles and pamphlets. But it was The Great Depression and his ninth book – The General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money (1936) – that made him famous.

Keynes was very critical of how governments generally addressed the depression. He fervently believed in an activist stance rather than a passive one. And he had a specific approach in mind.

Contrary to what is often asserted, governments weren’t necessarily passive or fuddy-duddy in the face of the depression. For instance, the much-maligned American president Herbert Hoover was a modern man of action with a long history of hands-on involvement in problem-solving and crisis management. And when the depression struck early in his term, he threw himself into a variety of rescue efforts, none of which were effective and some of which were counterproductive, such as the Smoot-Hawley tariff designed to protect American jobs.

Keynes, however, came at the problem from a different angle.

His central insight was that the economy wasn’t necessarily self-correcting. It could, in fact, stabilize at a level of activity way below its potential, thus leaving many unemployed and impoverished. The antidote was to pump up aggregate demand via large-scale government spending. And if this meant temporary deficits, so be it.

It was quite a while before Keynesianism took hold, but it had become orthodox thinking by the mid-20th century. And by the early 1960s, there were few dissenters in either the academic or political spheres. By the time he made it to the White House, John F. Kennedy was a convert to the idea of Keynesian demand management.

Keynes died in 1946, thus never getting to savour the full extent of his intellectual triumph. But neither did he have to deal with the later backlash.

People being what they are, an inevitable degree of hubris took over. Armed with Keynesian insights, professional economists and the politicians they advised came to believe in their ability to fine-tune the economy to permanently benign ends. With the technocrats and the experts in charge, all would be well. And because Keynesian economics was inherently friendly to activist government, politicians would be happy.

The Phillips curve was an example of this mindset.

Named after the New Zealander A. W. H. Phillips, the curve postulated a predictable inverse relationship between inflation and unemployment that would allow public policy to make a reasonably precise trade-off between the two. If unemployment was too high, economic policy should consciously tolerate higher inflation in order to bring unemployment down to the target level. And, if necessary, the opposite choice could also be made.

But it went spectacularly wrong. Despite the inverse relationship postulated by the Phillips curve, the 1970s experienced a severe case of what came to be known as stagflation. Inexplicably, inflation and unemployment rose together, and Keynesian orthodoxy was flummoxed.

Meanwhile, maverick economist – and 1976 Nobel Prize winner – Milton Friedman was chipping away at aspects of Keynesianism’s academic foundations, so much so that he’s often paired with Keynes as one of the 20th century’s two most influential economists. Then, in one of those twists and turns that bedevil the pretence of settled wisdom, Keynes came back into fashion in the aftermath of the 2008 financial crisis.

So what are we to make of all this?

One takeaway is that no single idea or perspective should be considered the solution for all circumstances. Modern economies are enormously complicated creatures and managing them requires a toolbox with many tools. Perhaps what Keynes described as a “general theory” is most appropriate to particular cases.

Another is that a touch of humility is always useful. To quote Keynes himself: “If economists could manage to get themselves thought of as humble, competent people on a level with dentists, that would be splendid.”

Troy Media columnist Pat Murphy casts a history buff’s eye at the goings-on in our world. Never cynical – well, perhaps a little bit.

For interview requests, click here.

The opinions expressed by our columnists and contributors are theirs alone and do not inherently or expressly reflect the views of our publication.

© Troy Media

Troy Media is an editorial content provider to media outlets and its own hosted community news outlets across Canada.