As Canada’s Washington ambassador, Allan Gotlieb, put it: “Trudeau believes the Soviets can do no wrong”

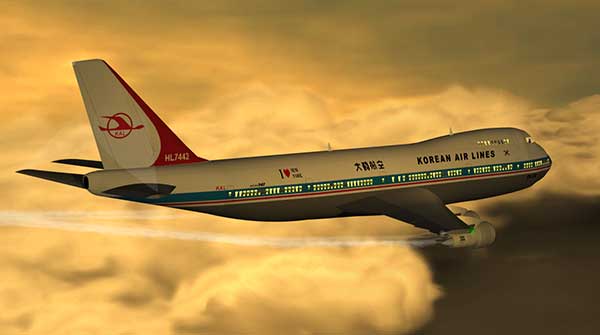

September 1 marks the 40th anniversary of a Soviet fighter jet shooting down Korean Air Lines (KAL) Flight 007, killing all 269 people on board. The plane – a Boeing 747 – had left New York City’s Kennedy International on August 31, stopped to refuel in Anchorage, Alaska, and then set out for its intended destination in Seoul, South Korea.

September 1 marks the 40th anniversary of a Soviet fighter jet shooting down Korean Air Lines (KAL) Flight 007, killing all 269 people on board. The plane – a Boeing 747 – had left New York City’s Kennedy International on August 31, stopped to refuel in Anchorage, Alaska, and then set out for its intended destination in Seoul, South Korea.

Instead, it ended up in the Sea of Japan at a depth of 571 feet. No bodies were ever recovered.

En route, the plane accidentally strayed off course into militarily sensitive Soviet airspace, where it was detected by radar and then tracked by an armed Soviet SU-15. The Soviet pilot was Gennady Osipovich.

Osipovich tried to contact KAL 007 by radio and failed, after which he fired warning shots. But it was dark, the rounds didn’t include tracer bullets and were thus unseen. So, under instructions to shoot it down, Osipovich fired two air-to-air missiles and KAL 007 crashed into the sea 12 minutes later.

Artist rendition of KAL 007 |

| Related Stories |

| Remembering the Cuban Missile Crisis 60 years later

|

| Mikhail Gorbachev, from global hero to forgotten man

|

| The unwelcome consequences of the collapse of empires

|

In a subsequent 1991 interview, Osipovich explained his action: “I saw two rows of windows and knew that this was a Boeing. I knew this was a civilian plane. But for me, this meant nothing. It is easy to turn a civilian type of plane into one for military use. I did not tell the ground that it was a Boeing-type plane; they did not ask me.”

When the news came, U.S. President Ronald Reagan was vacationing at his remote ranch atop California’s Santa Ynez mountains. This being serious stuff, he returned to Washington immediately.

Formulating the response had its complications. Although in international airspace, an American spy plane had been in the vicinity, attempting to monitor a rumoured Soviet missile test. Perhaps Soviet radar had confused KAL 007 with the spy plane.

For now, though, there were more immediate considerations. A two-track approach was chosen.

One track was a public response that would reflect the genuine shock and outrage while also deploying it to advantage in the ongoing Cold War battle for global public opinion. The other track was to prevent the situation from shutting down attempts at diplomacy.

Reagan himself took the lead on the first track, personally rewriting what he considered unsatisfactory speech drafts from White House and State Department wordsmiths. Then UN ambassador Jeane Kirkpatrick followed up with a Security Council presentation featuring audio intercepts of the exchange between the Soviet command and Osipovich. Responding to the argument that KAL 007 had violated Soviet airspace, Kirkpatrick had this to say: “Straying off course is not recognized as a capital crime by civilized nations.”

As for the diplomacy track, the Reagan administration decided to ignore calls to cancel the impending Madrid meeting between Secretary of State George Shultz and Soviet foreign minister Andrei Gromyko. Finding a way to constructively engage was critical to the long game.

Given their meeting of the minds on the Soviets, Margaret Thatcher’s support for Reagan’s approach was no surprise. Pierre Trudeau was a different matter.

Trudeau’s perspective had little in common with that of Reagan and Thatcher. Sharing none of their anti-communist fervour, he had an altogether more benign view of the Soviets. And deeply ambivalent about Canadian participation in NATO, he harboured a persistent distrust of the Americans. This general disposition was reinforced by the fact that the Canadian Embassy in Moscow “constantly counselled against provoking the Russians.”

Regarding KAL 007, sympathetic biographer John English notes Trudeau’s private belief that “the harsh response from the Americans had put the Soviet regime off balance and created their foolish response of initially denying the clear evidence of an attack.” Trudeau later went public, telling journalist Seymour Hersh that “it was obvious to me very early in the game that the Reagan people were trying to create another bone of contention with the Soviets when they didn’t have a leg to stand on.”

The shoot-down was almost certainly an accident facilitated by Cold War tensions and realistic concerns about spy planes. Had the Soviets realized that KAL 007 was an off-course civilian flight stuffed with passengers, it’s inconceivable that they’d have done what they did. It would’ve been all downside.

But the Soviet reaction went well beyond a hasty initial denial. They also impeded Japanese and South Korean search ships, concealed the fact that they found the wreckage, and generally stonewalled investigations.

Blaming the Americans for that seems a stretch. Perhaps as Canada’s Washington ambassador, Allan Gotlieb, put it: “Trudeau believes the Soviets can do no wrong.”

Troy Media columnist Pat Murphy casts a history buff’s eye at the goings-on in our world. Never cynical – well, perhaps a little bit.

For interview requests, click here.

The opinions expressed by our columnists and contributors are theirs alone and do not inherently or expressly reflect the views of our publication.

© Troy Media

Troy Media is an editorial content provider to media outlets and its own hosted community news outlets across Canada.